Alex put up this interview back in August. It's a great read! - BC

(cross posted at rocketshipstore.com)

Fred Van Lente has been a good customer and pal since the first day we opened the doors of the store. We've been on the sidelines to watch him finish writing his self-published ACTION PHILOSOPHERS, become one of the cornerstone creators of the all-ages MARVEL ADVENTURES line (including the hugely popular new POWER PACK series), and witness the rise of the INCREDIBLE HERCULES under his pen. HERCULES has been a sales juggernaut, and is one of the few books to come out of the WORLD WAR HULK event that has continued to gain momentum with fans. Last year's MODOK'S 11 was one of the year's best mainstream superhero comics, and currently, with a stove-top full of Marvel books on every burner, Fred has recently opened the self-publishing oven again with COMIC BOOK COMICS, a history of the comic book industry as drawn by his frequent collaborator, Ryan Dunlavey.

I always enjoy talking with Fred; he's jovial and funny, smart and insightful, and happy to talk about craft, and the process of writing for a wide range of projects.

ALEX: We've spoken in the past about writers using themes throughout their work, and having more to say than just the details of a plot. If you had to pick one overall thematic point that pops up when you write, what would it be?

FRED VAN LENTE: I'm interested in people the most, like most writers, and what informs their decisions. I strongly believe that the most interesting dramatic struggle is the one you have with yourself: The battle between what you want to do versus what you should do; when you should act versus when it would be better to do nothing at all.

That's why I like superheroes so much -- their powers and identities allow you to take internal battles and make them literal, they let you dramatize those conflicts. Hercules is the strongest guy in the world, but bears the weight of every foolish thing he's ever done -- and in 3,000 years, he's done a lot of them. Amadeus Cho's mega-smarts make him his own worst enemy. Wolverine is at constant war with his own bestial nature. And so on.

How does this modify itself when writing for older audiences versus younger audiences? Fiction versus non-fiction?

The only difference between kids and adults is what their specific pressures are. A kid feels being mocked in the schoolyard as keenly as a soldier getting shot at on the battlefield. One would never compare the severity of those two things, but as life is lived, the bullies coming in the kid's direction is just as important to his as the approaching bullet is to that soldier, even if it shouldn't be.

Likewise, history, to me, is the observation of changes over time. The historian tries to make sense of those changes as best he can, to build a coherent and, he hopes, accurate narrative to show how we got from Point A to Point to B to now-- how those changes informed the decisions of the people of the past, which then informed the next generation, et cetera.

Your collaborators run the gamut from one of your best friends/business partner, to people in other countries that you have very little contact with and have often never met. How do you feel that these relationships affect collaboration? Does the physical and personal distance between artists affect your relationship to the finished work? I'm wondering how different collaborations not only affect the process, but also your personal interest in the final work as "your own".

I think a comic book writer gives up the right to think of the final work as fully "his own" the minute he decides not to learn how to draw. (laughs) The very nature of my job means I have to be a collaborator, a team player. This seems to me to be where a lot of the contempt the funnybook intelligensia has for mainstream comics and mainstream comic creators comes from. The Academy demands "Art" with a capital "A", which requires an "Artist" -- singular. Writer/artists will always be praised over corporate freelancers in certain circles for that reason... It's no mistake that the Establishment didn't embrace films as "art" until the rise of Auteur Theory in France in the 1950s, which is predicated on the truly moronic idea that the director is the only important creator on a movie.

But do you ultimately feel less involved with the final version of a Marvel Adventures book? Do you deliver scripts to the aether, not really knowing how they'll return to you, after being passed through several stages of people that you may or may not know? Or do you continue to be involved after the script is done?

Actually, the process at Marvel I've enjoyed over my career means that I've been involved with every comic I've done with them every step of the way, regardless of my personal relationship with the artists involved, or whether we're working through a translator, or whatever. It's not as much control as on my self-published works like Comic Book Comics, you know, where I'm the letterer, so I can literally rewrite on the comics page right before we go to press... (laughs) And, also, there's more people to answer to in big, corporate comics. But that's okay. I've managed to figure out to do what I want to do within the framework of larger editorial control. I can only think of a couple times where I haven't (well, okay, once), but fortunately they've been minor, few and far between.

Speaking of Marvel, let's talk about the "personality" of their line. Marvel was built on stories that balanced grandeur and epic hyperbole with very intimate moments, and relatively realistic personal dynamics between characters. This was new and exciting in 1962, but now it seems taken for granted. The writers most associated with Marvel books tend to handle this balance easily, and often with great humor (Gerber, Kirby/Lee, Englehart, both Simonsons, etc). Do you consciously play with this dynamic?

Not consciously, but definitely those were the comics I grew up reading, and, frankly, the ones I still turn to read for fun now that I'm an adult and a pro. So I guess there's no helping the influence.

Lots of other people have said this better than me, but I think that to lose a sense of fun and adventurousness in superhero stories is kind of missing the point. It's almost like there's a certain segment of the superhero-reading populace that never got over the embarrassment of getting "caught" reading a comic, that never lost that suspicion they were reading what most in the mainstream saw as a children's genre. So unless their superheroes dress in leather, moan about their problems all their time, curse and kill people right and left, and live in "grounded" worlds (a term I've never understood -- or liked), the outside world won't think superheroes are "adult" enough. It's like little girls putting on mom's makeup and thinking they look more adult, instead of utterly ridiculous.

I'd like to think I'm from the generation that has gotten over these hangups about superheroes. I like superheroes, and I'm not ashamed to say it. We're out and we're proud! (laughs) We love (and, in some cases, create) books like Nextwave, Umbrella Academy, X-Statix, Doctor Thirteen: Architecture and Mortality, and so on, books that embrace and celebrate the inherent insanity of superheroes in a wonderfully un-self-conscious way, that manage to tell amazing stories about how we see reality, and how it affects us... Or, in some cases, just let us have a really great time.

Hell, I love superheroes so much I love grim-and-gritty too. The Ellis and Deodato Thunderbolts was pretty intense and violent, but I'd call it fun as hell at the same time.

It seems like a lot of fans resist the basic truth that many of these characters were created to entertain children. That's not to say that sophisticated stories can't be told using them, but in a very pure sense, a character like Superman or the Flash really shines when an eight year old can relate to them.

Well, I think a lot of fans don't see why their favorite characters can't age along with them. And there's nothing wrong with that. The superhero market couldn't survive without appealing to those "legacy" fans and making sure they have a reason to keep reading about their favorite characters.

But what I find baffling -- and mildly disturbing -- is just the oftentimes hysteric level of hostility I see out there against Marvel and D.C.'s all-ages output from some of the rank-and-file hero fans. The sheer amount of abuse heaped upon Power Pack in particular is just surreal. I saw an online reviewer say on a video clip he wanted to light it on fire and piss on it. It's one thing to not like it, or not think it's any good, but to go as over-the-top as some of these people go is just very bizarre to me. They just seem to hate it on principle, to hate the very fact of its existence.

Perhaps it goes back to what I was saying before -- this misguided evangelical notion that all superhero comics must "uplift" the genre in some vague, pseudo-sophisticated manner, to prove to the great invisible masses of non-readers out there that no, no, no, no, no, really, they're not for kids.

Fortunately, the abuse is well overcome by the kids and parents who come up to me and tell me how much they enjoy the work, or the postcards I get from them, or the one parent who told me he taught his autistic son to read using Power Pack because it was the only thing that engaged his attention. It's one of the more rewarding -- and surprising -- aspects of my career, because I never saw myself as becoming any kind of an all-ages creator.

With that in mind, let me ask you this; it seems that Marvel, moreso than DC, has a stable of characters that are perfect for slightly older adolescents. The problems they deal with are a bit more complicated; they've always seemed more operatic. How do you go about making Iron Man, for example, a character that is fun, without losing the more tragic sides to his character. (I realize those things aren't mutually exclusive, but I'm guessing it's more of a tightrope when writing specifically for children.)

The simplest way I find, is humor. I guess I'm inspired by Pixar's movies, which have an excellent track record of providing fun, adventurous stories for kids that adults can still find engaging, usually through gags that the average kid wouldn't necessarily get.

Do you find it difficult to maintain the balance of writing something that keeps you interested, and feels intelligent, but is still "safe" for a kids' line?

It's not the easiest thing in the world; there are a lot of hoops to jump through, and a lot of restrictions put on the material by the various competing interests, like Wal-Mart, etc. "Can this be packaged with a toy in C.V.S.?" and that kind of thing. "We need to put the next four issues in these covers because we're using them as a marketing push for so-and-so, can you generate stories to match?" And so on. I generally find those kinds of challenges really exciting. They do keep my interest up. But they can also drain you.

I'm actually going to leave -- or at least, take a sizeable hiatus -- from Wolverine: First Class after a year's worth of issues because I got little burnt out. There's a certain level of quality I'm not going to let myself drop below. At least not unless I'm starving or something ... and I'm not starving.

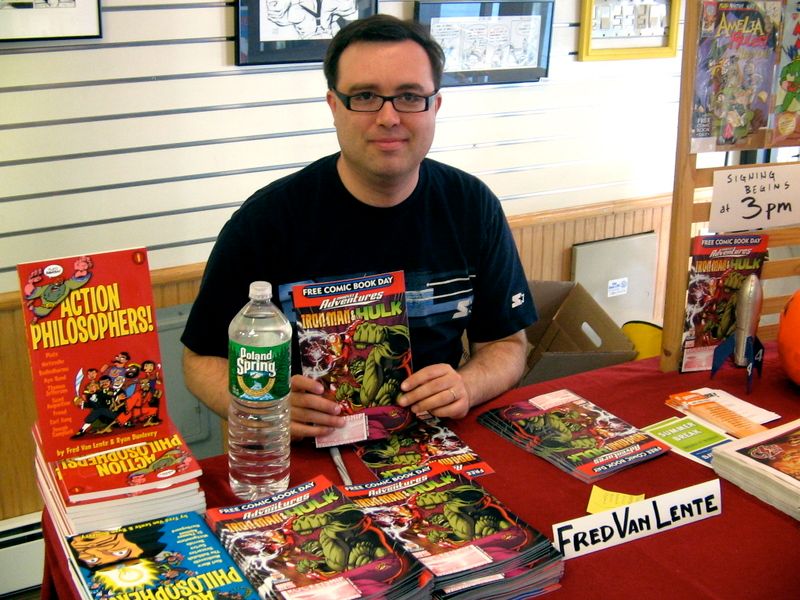

Fred signs for his fans. Free Comic Book Day '07 at ROCKETSHIP.

Let's talk Hercules. Traditionally, he has been portrayed as essentially Thor in a Better Mood.

Or, sometimes, "Thor in a Drunk Mood."

Well put! (Laughs) Hercules has always had fun-loving, hedonistic elements, but in many ways, he's a blank slate. Do you feel like you have left your mark on developing him into more of a distinct character?

Maybe. I'd be more comfortable saying I tried to put as many elements as I could from the original myths back into the Marvel version. Hercules was certainly a blank slate for me, as other than Bob Layton's terrific far-future minis, I didn't really know anything about the Marvel version of the character. So I just went and read all the myths, and really love them. It's been working with them that has been the most rewarding part of the series for me -- that, and getting to know Greg [Pak, Fred's co-author on THE INCREDIBLE HERCULES]. I think the Herc/Amadeus relationship has been way more interesting than either of us had anticipated at the beginning, too.

To continue with HERCULES... Grant Morrison has introduced Aurakles as the prehistoric, proto-superhero, and his importance in the DC Universe seems to be building with Final Crisis. Has the concept of Hercules as Ur-Hero crept your way yet? Do you think that the idea of primal, prehuman, mythical heroes is worth exploring in the Marvel Universe (aside from the Eternals)? Could Hercules be the right springboard for such a story? In short, has Morrison tapped into a concept that both universes could use?

Aaahhh, I think you may be onto something, Alex... But, alas, I cannot reveal too many details without tipping my hand as to the uber-arc of "Incredible Hercules" arc. Readers will be getting a big hint as to what that is at the end of "Incredible Hercules #120", on sale by the time folks read this.

All I can say is this: Perhaps the more interesting question is not 'is Hercules an Ur-Hero?', but 'is he palling around with the Ur-Hero to come?'...

I know that there are certain characters you have a affinity for, and characters you hate. Talk a bit about your favorite characters, why you like them, and what concepts they all share. What is it about certain characters that make them easier or more enjoyable for you to write?

Hercules and Amadeus we've already covered. I enjoy Machine Man, who's the star of [Fred-written, October-debuting] Marvel Zombies 3, because he's a really underappreciated Kirby creation. He's basically a regular guy who happens to be a robot. But that computer brain of his makes him not suffer fools gladly, and so he's an obnoxious wiseass. It's his love for Jocasta that ultimately redeems him.

She's kind of the other side of the coin, the robot who wants to do the right thing, to have humans like her. He's just like Inspector Gadget, except he can transform into railguns and flamethrowers! In the right hands (cough - mine) he could be a mega-hit.

Aaron is also, like a me, a connosieur of the malted arts. However, my spin on that is, again, because he's basically a computer with legs, he isn't a drunk, he's the biggest beer snob ever.

All of my favorite characters seem to be drunks. My wife is getting worried there's a pattern there...

A lot of your favorite characters also happen to be direct creations of Jack Kirby. I know you're a big Kirby fan; could you talk about what it is in his work that clicks with you?

I grew up reading a lot of classic 1960's Marvels in reprint, and as a kid I preferred the Ditko Spider-Man/Dr. Strange stuff more. But when I became an adult, it got a lot easier to get stuff like the New Gods in reprint, and that's when the Kirby bug really got me, in my late twenties. I desperately hunted down as much of his stuff as I could find. I think I finally understood that guys like Grant Morrison were coming from that tradition, guys that still influence my work, that inspired craziness of superheroes that I referred to before. Kirby was just a bottomless idea factory, an endless source of invention, and just the sheer act of watching him pull crazy concept after crazy concept out of his butt was just a dazzling performance to watch in and of itself. Particularly if you've read as many goddamn superhero comics as I have (laughs), there's something exhilarating at how this guy kept reinventing and reinventing the genre, right up to the end of his life.

Even though I am an unabashed Kirby partisan, however, it's hard to not to agree with the main thrust of a lot of the criticism aimed against him, that his ear for dialogue was ... er, unique, to say the least. It certainly seems to be have been formed partly by memories of old Hollywood movies and, in a horribly ironic way, trying to parrot Stan Lee without really quite getting what Lee was all about.

A lot of Lee's Spider-Man and Silver Surfer and Thing monologues come from a very honest, wounded place, as bombastic and perpetually optimistic the huckster "Stan Lee Presents" side of him always is. Kirby, on the other hand, it just seems to me, had very little interest in individual humans. He was interested in HUMANITY as a concept, and abstract ideas like TYRANNY versus FREEDOM, but they found expression almost exclusively in metaphorical ways, like the conflict between Darkseid and Mr. Miracle.

And so I can't blame people when they say they don't get non-Lee or non-Simon Kirby. I honestly believe it's the same thing as people not liking abstract art. I dig Mark Rothko. But a lot of people look at his paintings and say "It's just blocks of color. My 6 year-old could do that. What the fuck?" Even some of Kirby's best stories, like "The Pact", lack a real genuine human connection. The relationships are more conceptual and symbolic, like mythology, which has this real kind of stream of consciousness narrative, not like a a short story or TV show at all.

That's why it excites me to work with obscurer characters like Machine Man and M.O.D.O.K. and Hercules, Kirby characters that are just so brilliant in conception that you don't need to do much to give them that extra humanity to broaden their appeal to a wider audience.

Let's take a half-step over, from M.O.D.O.K. to Sartre (Laughs). Were there any famous thinkers that were left out of ACTION PHILOSOPHERS, and you regret not including them? What criteria did you use to include someone?

They had to be pretty famous. I had a couple philosophy textbooks and surveys on hand and basically just checked people off like a laundry list. There were a couple people we didn't do that could have borne inclusion. Epicurus we didn't do because of the William Messner-Loebs and Sam Kieth books. The one people keep asking about is William James, the 19th century American pragmatist, who I don't really know much about. I really wanted to do the medieval Sufi poet Rumi, just to add a Muslim among the Christian, Buddhist, Taoist and Jewish thinkers we had in there. When we do the Complete Action Philosophers collection (out in time for Christmas 2009!) I think we'll throw those in there as brand-new stories for completion's sake... And, you know, to trick people who already have all the issues to buy the hardback. (laughs evilly)

If you had to pick one philosopher from the series to do a full book about, who would it be?

Hmmm... A complete GN about one philosopher... I don't know. I got my own ideas about The Big Questions from reading all those thinkers, and one day I might inflict my own philosophy on the world, if I can think of a way to do it without sounding like a pretentious windbag. (Too late, har-har...)

Both ACTION PHILOSOPHERS and COMIC BOOK COMICS required huge amounts of research. As we finish up here, tell me about the most surprising things you've found in your research about comics history.

There's a lot! How the underground artists influenced the French creators who founded Metal Hurlant, which, of course, turned around and had such a huge influence on these shores... That Jerry Siegel was inspired by the fights in "Popeye" to make "Superman"... That ABC-TV felt so indebted to the Pop Artists for the Adam West "Batman" TV show that they arranged to have a premiere party of the show for them... COMIC BOOK COMICS is chock full of those kinds of nuggets. It's the most rewarding part of creating the series.