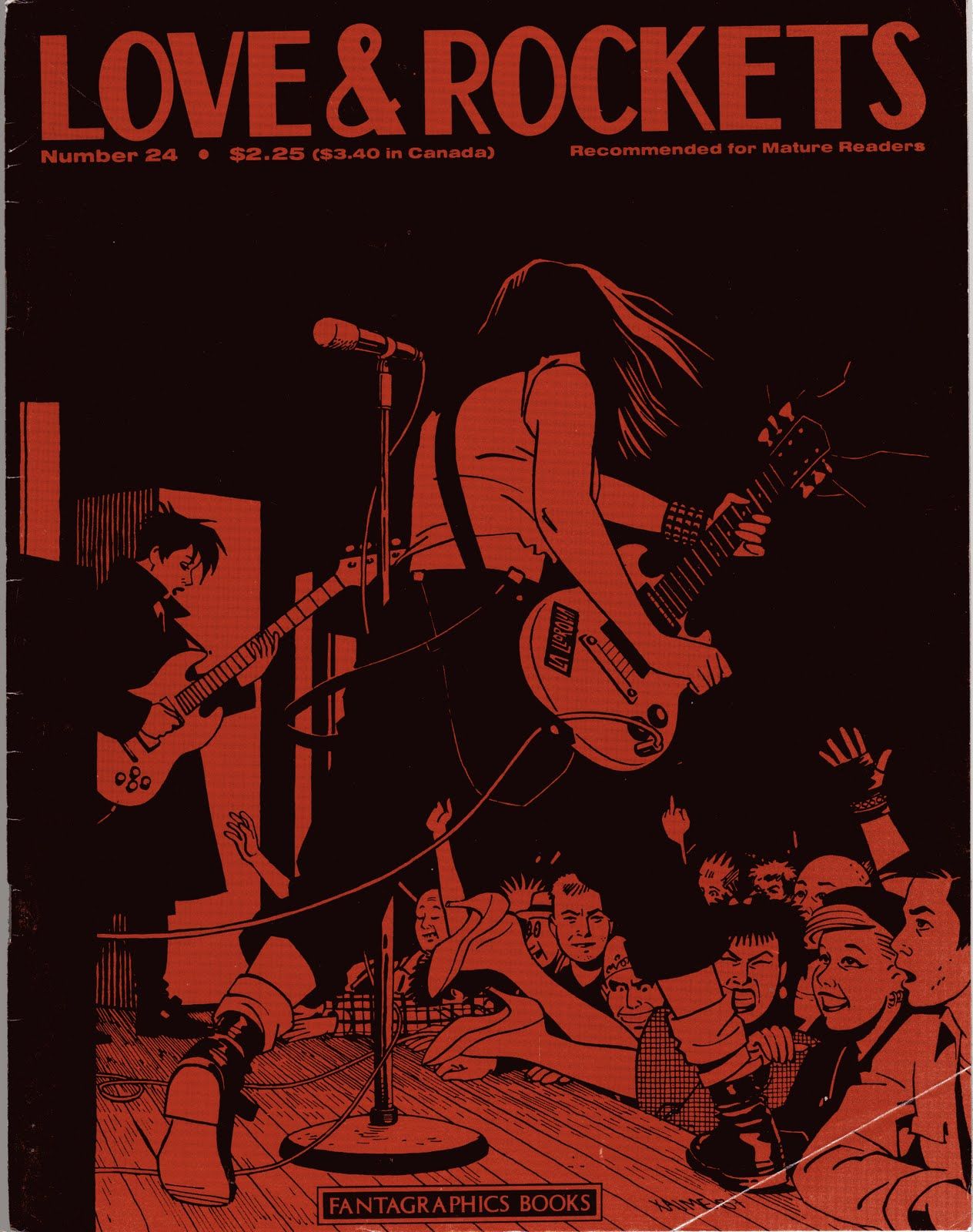

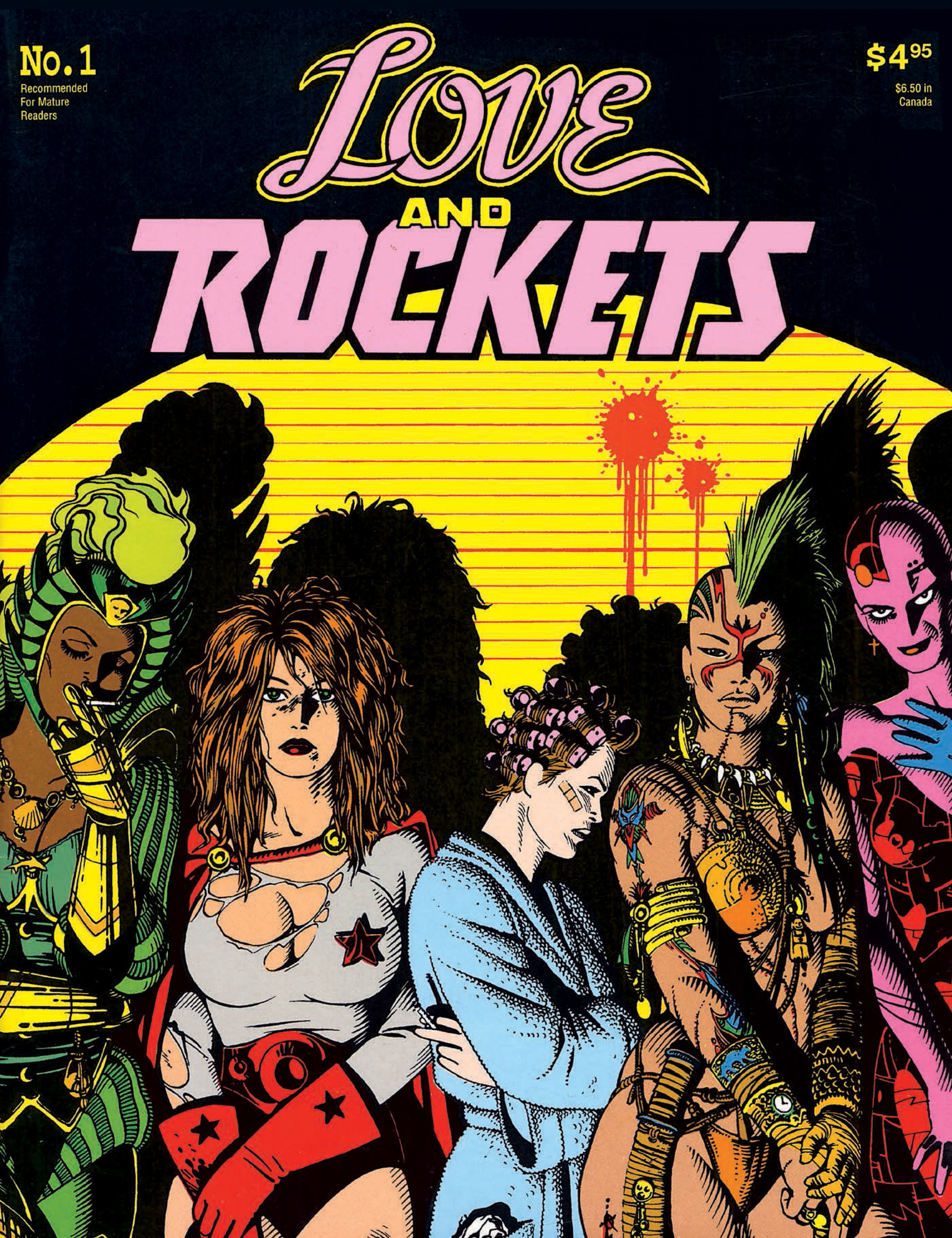

Hitting the 30th anniversary of your career in comics is always worth celebrating given the medium's tendency to chew up and spit talented people out (speaking of which, did you see that Graham Chaffee has a new book out?) That's doubly true in the case of the Hernandez brothers, as Gilbert and Jaime (and sometimes Mario) have not only been able to stay in the game despite the various radical shifts in the landscape, they've been able to produce challenging, thoughtful, emotionally powerful comic consistently over the course of those three decades with nary a drop in quality.

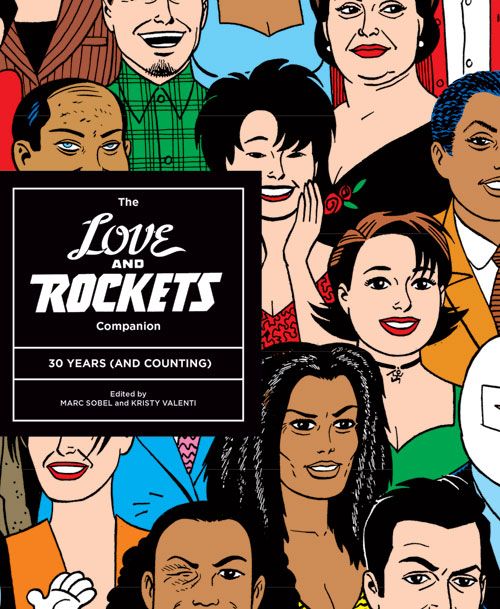

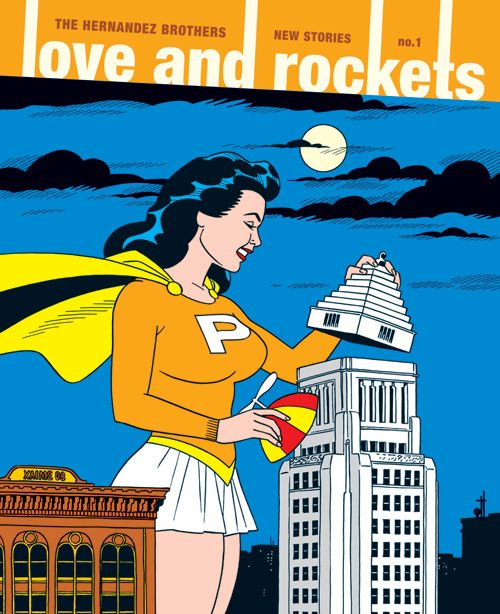

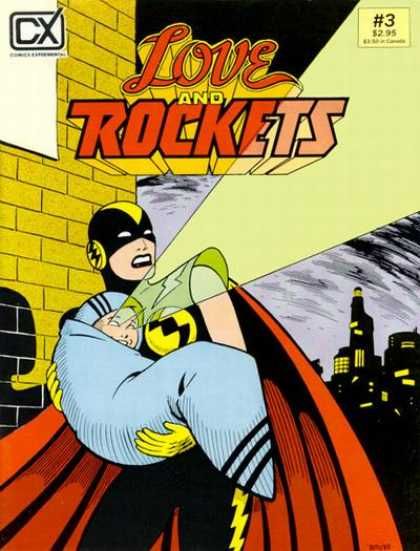

Fantagraphics is celebrating the anniversary with a trio of books the focus squarely on the brothers' signature title: The Love & Rockets Reader and Love and Rockets: The Covers – both due out later this year – and The Love and Rockets Companion: 30 Years (and Counting) the latter of which, co-edited by Marc Sobel and Kristy Valenti, just came out this past week. It's an impressively thick tribute to L&R, featuring three lengthy interviews with the cartoonists, a complete list of characters in both Jaime's Locas series and Gilbert's Palomar saga, a timeline of the stories, an issue checklist and even a selection of highlights from the letter columns. In short, it's the perfect scrapbook to some of the best comics ever made.

Sobel is the perfect person to be help shepherd this book: He's written at length about Love & Rockets for Sequart (and the bulk of those essays will appear in the L&R Reader), and always with insight and intelligence. I talked with Marc over email about the book, how it came together and why it's important to celebrate and discuss the Hernandez brothers' work to such a degree. I could have kept the discussion going for days.

How were you initially introduced to Love & Rockets?

As a lifelong comics fan, I was aware of Love & Rockets for years, but I was too young when the series started and then I was just always reading new comics, so I never went back and checked it out. But around 2006, after a few years of writing reviews online, I decided I wanted to school myself in the classics of the medium so I would be a better, more informed writer, and I could enjoy higher quality comics, instead of just always following the latest fads. I decided to start with Love and Rockets because I found someone selling the entire 50 issues of volume 1 on eBay for cheap.

What was the first issue/story you came across? What was your initial reaction to the Hernandez brothers' work?

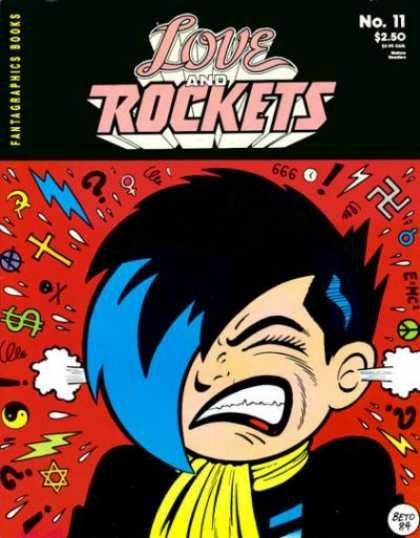

I started with issue one and worked my way through the series. I wanted to recreate the experience of reading the comics as they came out, as opposed to the trade paperbacks. I also thought reviewing each issue as I went would make for a fun blog project. So I did that for the first 25 issues or so and it ran as a semi-regular column on Sequart.

Right from the start, I liked both brothers’ work a lot, and because I was writing about each issue, I was really looking at each story closely and analyzing everything. One of the first stories that really struck me as something special was Jaime’s How to Kill A… By Isabel Ruebens. Not only is it a visual masterpiece in terms of its depiction of writer’s block, but there was clearly the seed of a fascinating character buried in that four-pager that made it stand out. Then Gilbert’s opening chapter of Heartbreak Soup in the third issue felt like the flood gates had been kicked open. I could tell even in those early issues that this was a special series, but of course, I had no idea what was ahead of me at that point.

How did the Companion take shape initially? Was this a project you brought to Fantagraphics or did they come to you?

The initial plan was that Sequart was going to publish the book, but then they experienced an extended outage that lasted for several months, and by the time the site was restored, I had lost my motivation to keep posting it online. So I took a long break from it, almost a year, but eventually I realized I really wanted to finish it so I started working offline.

I know the folks at Fantagraphics were aware of my work because as I was originally posting each review they would occasionally link to my columns from their blog. Tom Spurgeon was also great about pointing people in my direction. I was even getting some sporadic fan mail which, as a critic, I had never had before. So I was really encouraged by the positive response, but I also just figured I had to keep going and finish it before talking seriously to any publishers.

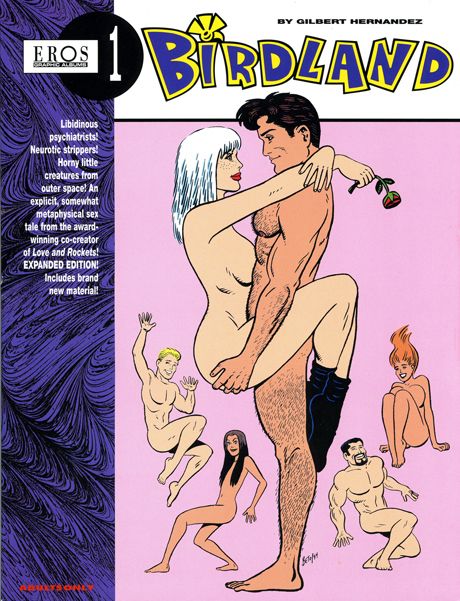

Then, when The Comics Journal re-launched its website for the first time back in 2009, I think, I was fortunate to have my essay on Birdland as a featured post that ran the entire first week in five parts. I think that essay was a turning point which caught people’s attention. Not long afterward, in 2010, I met Jaime and Eric Reynolds at MoCCA and that’s when we first started talking about the possibility of getting a book together for the series’ 30th anniversary.

What was the most difficult aspect of getting the book together? The timeline? The character list? The interview?

The timelines were definitely the hardest, but each part had its own challenges. The character lists were pretty straightforward, although they took a lot of time. Chris Staros had published some pretty good character guides back in ’96 in his fanzine, The Staros Report, and he was kind enough to share these with me, so I at least had a starting point. But I still had to update them, add first appearances, and extend them to cover an additional seventeen years worth of stories.

How did the family tree poster on the inside cover come about? How difficult was it to execute?

The family trees, especially the one for Jaime, were very complicated, and we went back and forth several times with the Bros and the designers trying to get them exactly right. I started by going through the entire series very carefully and making detailed notes about each character and their extended families, siblings, lovers, etc. Then I tried to do an initial chart in an Excel spreadsheet using arrows and notes, but that turned into a mess, so I had to rework it several times just so it would make sense to someone besides me. When I finally got a decent draft, we sent them to the Bros to edit. But really the real credit goes to Tony Ong and the designers at Fantagraphics who turned my notes into the beautiful charts that are in the book. They did an amazing job!

How did the timelines come together? Were you able to collaborate with Gilbert and Jaime on them? Were there parts where things seemed to contradict?

The timelines I put together myself, and then I sent them to the Bros. In Jaime’s case, I think he had a pretty good sense of whether I had things straight or not, particularly as they pertained to Maggie’s family, but he sent me some pretty detailed notes. Also, for Jaime’s early stories, there was a draft of a timeline that a fan named Mark Rosenfelder had posted online, so that was a helpful starting point.

For Gilbert, on the other hand, doing a timeline was very challenging. For one, he has a lot more stories to integrate, and for the most part, I don’t think Gilbert really uses a timeline for his stories. The only exception is Poison River, which has a very definite timeline, and since that story ends with the beginning of Heartbreak Soup, I was able to impose a timeline on the rest of the Palomar stories. But I admit parts of the Palomar timeline, particularly the Fritz stories, are just estimates.

Why did you decide to include the letters columns? What was the importance of those correspondences that you felt it worth reprinting in the book?

The letters column highlights was something I thought would be a fun little bonus feature for people who had only ever read Love & Rockets in trade paperbacks. Since I read the series in its original issues, the letters columns were a big part of the whole experience and I really enjoyed seeing the intelligent and insane reactions the series got. So I just thought it would be fun to include some of the best letters, but we chopped it down quite a bit.

In re-reading and scrutinizing the Hernandez brothers' work for this book was there anything that surprised you? Were there any new discoveries? Or re-discoveries for that matter?

Well, a lot of the detailed stuff that really surprised me regarding particular stories is in the Reader, which contains all of my detailed analysis and research; whereas the Companion is more like the bonus features on a DVD. But in working on the Companion, I was surprised how many characters Jaime has created (over 500!). I would never have guessed that he had about the same number as Gilbert. I was also surprised at how cohesive Jaime’s Locas saga is on the whole. Sure, there are a few little things that someone looking as closely as I did will notice, but they’re very minor stuff.

I don’t want to slight the efforts of your co-editor, Kristy Valenti. How did the two of you divvy up the work? Who did what?

Initially in my mind the Reader and the Companion were one book, and it was really Kristy and Eric who suggested splitting it into two. How could I argue with that? Plus, in hindsight, it makes a lot of sense since there was way too much material for one book. They also asked me to add some stuff including the character guides and timelines which were not part of my original plan.

I did the initial drafts of almost everything in the Companion (except the Groth and Gaiman interviews obviously) and then Kristy edited, fact-checked, and compiled it all. Plus, she and her interns transcribed the new interviews, which I edited with the brothers. She also worked with the graphic designers to figure out what images and captions to include, and the overall layout and presentation of the book.

What was it like collaborating with her on a project like this?

Kristy was great to work with, and we’re actually not done working together since she’s the editor on the Reader, too. In my mind, she’s the perfect partner for these books because not only is she a great writer about comics herself, she’s also a huge fan of the series. So right from the beginning I think we shared the goal of trying to celebrate the Hernandez brothers’ incredible milestone as best we could.

She was also extremely helpful in planning for the interviews. Normally, when I do comics interviews I try to get the artists to tell their own story, how they got into comics, their background, training, ideas, process, etc. But with the Bros, that didn’t make sense since they’ve talked about all that stuff in dozens of other interviews. I knew if I wanted to keep them engaged, I had to come up with questions they’d never heard before, but that was a major challenge. Plus, since we were reprinting Gary and Neil’s old TCJ interviews in the same book, it didn’t make sense to go into much of their background since that was already well covered, too. So we decided to focus on their more recent work, and try to get them to reflect on their careers in general. Planning and figuring it all out was a lot of work, and Kristy was a great sounding board.

In the interview you did with the brothers, I sensed a certain bitterness, or at least snarkiness, from them aimed at both their critics and the contemporary comics scene. Is that accurate?

People can judge for themselves, but I’m not sure how much of it was bitterness vs. their punk attitude of ‘I’m gonna do whatever I want and fuck whoever doesn’t like it.’ Maybe that comes across as snarky, but it’s served them well over the years and they’ve certainly earned the right.

Do you agree with Gilbert that people seem to have a more hostile reaction to his recent work and if so, why do you think that is?

I think part of why Gilbert gets mixed reviews is because he didn’t continue doing Palomar stories, although he does still do them from time to time. Even though people always say they want artists to grow and change, the reality is that some people don’t really want that. And that issue was magnified by the fact that Jaime did stay the course with Locas. Gilbert’s work also has an edge to it that can be a bit abrasive, even though it’s honest. He’ll attack critics or mock people who try to dictate what kinds of stories he should do.

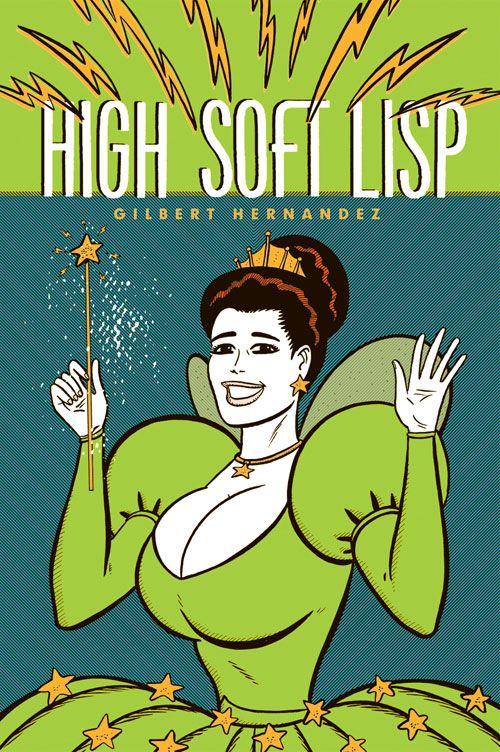

If you really stop and think about it, an artist’s integrity is his greatest asset. Some comics fans think they have a say in the creative process because that’s the way superhero comics work, but independent artists like the Hernandez brothers have to be true to themselves and follow their impulses. Gilbert’s well aware that his stories may not work for everyone, but if he’s going to sit at the drawing board for weeks on end devoting his heart and soul to a project, he has to feel passionate about it. I really admire his conviction and I also think it’s allowed him to produce some amazing non-Palomar stories which are sadly under-appreciated.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about Love and Rockets?

Probably what we just talked about, that Gilbert’s more recent work is somehow inferior to his older work. It’s hard to convince people, but Gilbert’s doing some of the most amazing crime noir and surreal fantasy comics ever created. I’m confident that time will be kind to Gilbert and people will eventually start to recognize that stories like Sloth, Chance in Hell and Hypnotwist are brilliant comics.

The other misconception I hear sometimes from younger fans and artists is that “you had to be there” to appreciate Love & Rockets. It’s like they’re aware of who the Bros. are and recognize what their work meant for the industry, but they’re either too lazy or too overwhelmed to actually read it. Obviously I don’t agree with this. I think Love & Rockets is a timeless classic, and the stories are still rich and rewarding thirty years later as they were back in the 80s.

Pretend you're talking to someone completely unfamiliar with Love & Rockets. What is it about Gilbert, Jaime and Mario's work that is so captivating and worth reading?

There are so many things that make it a great series. I guess I’d say that Love & Rockets is one of the best examples of intelligent comics. It’s the perfect series to give to open-minded readers who are not strictly comics fans.

Jaime’s stories are focused on a diverse cast of fully realized characters with deep, complex inner lives. The fact that these characters age in something resembling real time in the stories has allowed readers to form intensely personal bonds with them. That reader loyalty is unprecedented in comics, but wholly earned and respected by the artist.

Gilbert’s stories about Palomar also have that personal, human quality, but Gilbert has so much more to offer. He’s a fascinating, multi-faceted artist who’s proven he can deliver quality stories in many different genres. He’s as comfortable telling zombie slasher stories as twisted silent b-movies. He’s got a bit of R. Crumb’s underground vibe to his stories at times, and other times can capture the pure joy and innocence of childhood. On top of that, both Hernandez brothers are extremely talented and imaginative illustrators, some of the best draftsmen in comics.

Love & Rockets also broke new ground with its ethnic depictions of Latinos, authentic depiction of the Southern California punk scene, and its realistic portrayal of sexuality and gender roles. It also inspired a new generation of alternative cartoonists to break free from the corporate-owned properties and traditional genres, and to pursue their own artistic visions. Love & Rockets is also a unique American success story. The fact that these two punk, Mexican-American brothers created a series that has sustained thirty years of success in an extremely fickle industry like comics underscores its legendary status.

What starting point would you recommend for new readers?

I know that new readers are sometimes intimidated by the sheer volume of material and the accumulated history of the stories, but I encourage people not to let that deter them from experiencing one of the greatest series ever created. I’d actually encourage new readers to just dive in anywhere if you’re curious. Don’t feel like you have to read everything, although you will likely want to after you start. If you do want to attempt to read the entire series, which I obviously recommend, then the logical starting point is either Jaime’s Maggie the Mechanic or Gilbert’s Heartbreak Soup. These are collections of the brothers’ earlier works, but there’s plenty to enjoy. I’d also refer them to the reader’s guide on Fantagraphics website, which is very thorough.

OK, without thinking: Personal top five Beto and Xaime stories. Go!

If we did this ten times, I would probably come up with different answers each time since I admire and love so many things about different stories. But for right now I’ll say:

Jaime: Flies on the Ceiling, The Love Bunglers/Browntown, 100 Rooms, Chester Square and Spring 1982.

Gilbert: Poison River, Ecce Homo, Bullnecks and Bracelets, Human Diastrophism and Hypnotwist.