All-New Doop (Marvel): It's perfectly appropriate for any series starring peripheral X-Men character Doop to be a weird one, however, the miniseries collected in this trade paperback is weird in a weird way.

Doop was created by writer Peter Milligan and artist Mike Allred for their iconoclastic (and somewhat -controversial) 2001 X-Force run, which was then relaunched under the name The X-Statix. The premise involved a group of celebrity-wannabe mutants who used their powers for fame and fortune by starring in a reality show; holding the camera was a mysterious, gross, floating, potato-shaped green creature that spoke its own, indecipherable language and answered to the name Doop.

Milligan imagined a dramatic behind-the-scenes life for the character in a two-part, 2003 Wolverine/Doop miniseries, and writer Jason Aaron ran with the joke, including Doop as a member of the faculty at the Jean Grey School during his Wolverine and The X-Men run. For the most part, Doop functioned as a background joke, one more signifier of the zany environment of the new school for young mutants, though Aaron did pair with Doop's co-creator Allred for a one-issue story that focused on the character as a behind-the-scenes, floating potato-thing-of-all-trades.

Milligan returns to the character for this miniseries, in which Allred only provides the covers, while David LaFuente draws the majority of the art. Milligan takes Doop's behind-the-scenes portfolio to an extreme, marking him as a character capable of traveling through "The Marginalia," entering and exiting the comic-book tales in order to influence their outcome.

The story Doop influences here is "Battle of the Atom," the Brian Michael Bendis-helmed X-Men crossover that involved Cyclops' X-Men team, Wolverine's X-Men team and an X-Men team from the future engaged in a fight over what to do with the teenage original X-Men plucked out of the Silver Age and currently hanging around the present.

That story ended with Kitty Pryde making a pretty random choice that didn't make any sense within the context provided, although it was the climax of the whole storyline. With All-New Doop, Milligan seems to be engaged in retroactively justifying her action, with Doop telling Kitty she must "find he courage to be ... irrational" early on in the series, long before she makes her choice.

Oh, yeah, Doop talks in this. Like, actual, intelligible English. It seems to be a major violation of one of the character's key charms, but so too is the entire series, as it treats the events of the Marginalia, Doop's world, as the A-plot, and the events of "Battle of the Atom" as the B-story. Your enjoyment of the series is thus dependent on how familiar you are with "Battle," as Doop interacts with various players in the series — Kitty, Teenage Scott and Jean, Iceman, Raze, Wolverine — as he swerves in and out of the events of the series.

Milligan also spends some time detailing Doop's past, including his parentage, a secret origin that turns out to be one of those "everything he thought he knew was wrong!" staples of superhero comics, and his real origin, which involves a revelation of his true gender (pay no attention to the male pronouns I've been using throughout to refer to Doop, please). That too seems like something of a betrayal of Doop's charms, as it dispels so much mystery.

If what's funny about the character is that we can't understand him, we don't know what exactly he is or what he does and he only appears in small, carefully regulated doses, well, All-New Doop tears down all those attributes. But then, he's Milligan's character — in terms of a creator-created relationship, if not actual ownership – and if that's what Milligan wants to do with him, I suppose that's his right.

Lafuente isn't the first artist who wasn't Mike Allred to draw Doop, but his version is markedly cuter than the one Allred, Darwyn Coooke, Chris Bachalo, Nick Bradshaw and others have depicted in the past. Lafuente is a great artist, and his open, engaging style is a welcome presence when it comes to re-drawing all these X-people and their scenes from "Battle," but his big-eyed, big-handed, little-mouthed, human-expression-having Doop comes in sharp contrast to the more alien, inscrutable look of previous incarnations.

Fans of X-Statix and/or Wolverine and the X-Men who also read and remember "Battle of the Atom" quite clearly will likely get a lot out of this trade, but that's a rather narrow audience ... even by the standards of X-Men comics.

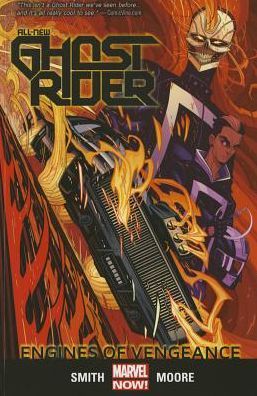

All-New Ghost Rider Vol. 1: Engines of Vengeance (Marvel): This trade paperback collection of the first five issues of writer Felipe Smith and artist Tradd Moore's reinvention of Marvel's Ghost Rider, whose popularity waxes and wanes by the year and the direction, certainly earns the "All-New" part of its tite.

It's not just that the creative team introduces a new "host" to the title character, beleaguered Los Angeles high-schooler Robbie Reyes, who's raising his special-needs little brother in a horrible, crime-ridden neighborhood all by himself (and whose teenage problems make those of Peter Parker at his age seem downright trivial). It's not just that this is apparently also a new Spirit of Vengeance that inhabits Reyes. It's not even that this Ghost Rider's flaming vehicle is a car instead of a motorcycle.

While all of that certainly helps distinguish the new series, more than anything its Moore's artwork that makes All-New Ghost Rider look, read and feel all-new. It's really unlike almost anything else Marvel or its main competitor are producing at the moment.

Moore's character designs are all incredible, bordering on inspired, from the primary characters to more minor villains, like Marvel Universe mainstay Mr. Hyde (who doffs his Victorian coat to simply rip out of his clothes, Hulk-style, and is given Japanese ogre fangs and long, sinister eyebrows) and a neighborhood drug dealer who overdoses himself on super-steroids, eventually growing multiple arms.

All of Moore's characters are super-expressive, their faces occasionally warping when they're conveying high emotions, and all are so broadly and effectively drawn that one could read the comic without any dialogue balloons and not only follow the action, but also most of the drama. The one exception is the title character, whose face isn't a flaming skull, but a flaming metal sculpture of a skull. This Ghost Rider has a face as unchanging as a hood ornament.

Where Moore really excels, however, is in rendering action, from the car races and chases to Robbie getting massacred in a hail of bullets in the first issue (don't worry, he gets better), to the many rather amazing super-battles, Moore's Ghost Rider is easily the most dynamically drawn comic on this side of the Pacific.

Unfortunately, Moore has already left the book, his run only lasting as long as the issues collected herein — his run therefore is even shorter than Declan Shalvey's on Moon Knight. As with the Moon Knight collection discussed last week, this book reads perfectly well on its own. But unlike Moon Knight, the writer of Ghost Rider is sticking around after the early departure of his artistic partner. Given how integral Moore was in making this book as good as it is, his departure would normally be quite alarming. His replacement, however, is Damion Scott, who has a similar highly dramatic, in-your-face style of action and acting; if anyone can follow Moore, it's probably Scott. I guess we'll see in Volume 2.

Batman Vol. 5: Zero Year—Dark City (DC): I pretty clearly remember my reaction when DC solicited the first issue of this epic storyline focused on Batman's origin. Given how popular, influential and even celebrated Frank Miller, David Mazzucchelli and company's "Batman: Year One" was — I'm certain that "Year One" was at least a factor in DC's decision not to do a hard, start-from-scratch reboot with The New 52 — that any attempt to revisit, rewrite or overwrite parts of it struck me as audacious. To deliberately echo it in your title just seemed like pointing at the fence when entering the batter's box.

This book collects the second half of "Zero Year," and thus concludes the story. I'm as happy as I am surprised to be able to report that Scott Snyder, Greg Capullo and Danny Miki hit it out of the park.

A direct comparison to "Year One" doesn't do either book any favors, and, honestly, I don't know how one would decide which is "better." It doesn't look as if Snyder was interested in that, anyway; without too much difficulty, a reader could probably reconcile the two stories in one's head. If nothing else, Snyder doesn't overwrite "Year One" at all — many of the same characters obviously appear, but few of the same events do.

And the events of this particular collection are all set after the origin business, and are concerned with the first time Batman and his allies pulled Gotham out of a semi-apocalyptic situation, and solidifying Bruce Wayne's definition of, acceptance of and dedication to his mission.

I don't want to drone on about this already justly praised storyline — which, at 12 issues, is maybe the longest single Batman story arc by any single creative team in one of the regular series — so let me simply be contrarian and point out two things I didn't like about it, because I'm that sort of person.

First and foremost, the bit about the end, with Batman literally restarting the power in Gotham City with his own heart was a bit ... much, I thought. All of the action leading up to that point already hammered home how integral Batman was to Gotham, without that particular lily needing gilded.

Secondly -- and this is more a question and a reservation than a criticism -- I was somewhat taken aback by The Riddler's massive presence in Batman's career at such an early point, emerging as a master criminal before the likes of The Joker (as The Joker, The Red Hood dominated the first half of "Zero Year"), The Penguin (who appeared, but in a minor role), Catwoman, Two-Face or The Scarecrow — all characters who appeared historically before The Riddler.

Such fiddling is nothing new, of course. Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's equally epic miniseries The Long Halloween and its sequel Dark Victory used The Riddler, Poison Ivy and other characters who debuted long after Robin in a "Year One" story; I just wonder if there isn't something to honoring the "real world" history of the characters when crafting their fictional stories.

That said, "Zero Year" is such a Riddler tale, it's hard to imagine swapping him out for anyone else without completely changing the story, but there was a buzzing in the back of my head while reading some of this, saying The Riddler probably doesn't belong in it, you know?

But that might have just been me. "Zero Year" was still a home run, as unlikely as it might have seemed when I saw Snyder and Capullo coming up to bat.

Beauty (NBM): A newly translated and released original graphic novel featuring art by Kerascoët, the artists behind this year's Beautiful Darkness, Beauty deserves attention for that fact alone.

While not as disturbing or subversive as Beautiful Darkness (God, what is?), Beauty is similarly a rather dark, mature fairy tale, one that reminded me of some of Osamu Tezuka's work in European fairy tale-like settings, only with sharper edges and fewer jokes.

Beauty is the story of Coddie, a big-eared, bug-eyed young woman who spends so much time scaling fish that the stink of them has permeated her skin. Obviously this makes life hard for an adolescent, and working as the servant girl of a particularly cruel and imperious woman doesn't help matters.

Things get "better" when she accidentally frees a fairy from a curse, and is granted a wish. She wishes for beauty, and while the fairy says she can't change nature, she can change the perception of nature: "In the eyes of others, you will be the very idea of beauty in woman incarnate."

Much of the rest of the book is a master essay on being careful what you wish for, as the men of her village are driven mad with lust and attempt to rape her, the women of the village try to destroy her beauty by scarring her with hot coals and, in the ensuing madness, her mother is killed and only the intervention of the local lord saves Coddie.

Although he makes her his, he too is driven mad by her beauty, which soon plunges the whole known world into turmoil, as Coddie moves from lord to king, ruins his kingdom and drives him mad, and, once seen by a rival ruler, plunges the two countries into war (while the milieu is clearly European, there's obviously a touch of the Helen of Troy story here as well).

Kerascoët and writer/colorist Hubert deliver an epic, if cynical, graphic novel meditating on the pettiness of human (and fairy) nature, and how lust and jealousy make the world go round. Eventually Coddie, renamed Beauty, learns her lesson, helped along by the birth of a clever daughter who helps her grow up immensely, and lashes back at her one-time fairy benefactor. It doesn't end happily, but those who survive at least manage to live more wisely.

There's also a pretty awesome epilogue that takes a pin to the concept of beauty standards. Like the book that precedes it, it's extremely sharp and incisive.

In a Glass Grotesquely (Fantagraphics): The words "Selected Picture Stories by Richard Sala" appear below the title of this book, promising something of an anthology. And it is an anthology, at least technically, although given that a single story takes up 115 of the book's 135 pages, it reads much more like a graphic novel with a few short back-up tales.

That 115-page graphic novel is "Super-Enigmatix," the name given to a mysterious but omnipresent evil influence, a so-called "master fiend" who sits like a secret spider in a web comprised of all the crime in the world. Super-comics fans might read that description and think of one of the bad guys in Grant Morrison's Batman comics, and, indeed, Sala's design for the character echoes that of classic Batman foe the Red Hood: Super-Enigmatix wears a sharp suit and disguises himself with a red hood and cape, through which only his eyes can be seen.

Sala's influence here seems to be old movies much more so than superhero comics, old or new — although that is, as always, filtered through the cartoonist's uniquely macabre and semi-sardonic style.

"Come in. I've been expecting you," one of the lead characters says on the first page. "Naturally, since I just called to tell you I was on my way over," is the answer he receives from the main character. The pair are among a small group trying to untangle Super-Engimatix's web, and reveal him to the world. The attention only makes he and his schemes bolder, however, and he launches a wave of strange, apocalyptic attacks on various cities and groups of colorful victims, including a secret, corrupt cabal not unlike the one that figures prominently in Sala's post-apocalyptic Frankenstein riff The Hidden.

Imagery and motifs familiar to Sala's previous work surface throughout — a remote village, monster men, beautiful young women in short dresses or tight suits, costumes, attacking animals, etc. — but the heart of this tale seems to be rather heavily inspired by vintage spy films, Super-Enigmatix scanning like a Fantomas-like Bond villain, complete with an elaborate secret headquarters staffed by young ladies in sexy uniforms. (So pronounced is the film influence that even when the title character shoots a victim at point-blank range in one panel, when her dead body is shown sprawled on the floor in the next, she doesn't even have a wound, let alone gore pouring from it; it's a very old-school, TV Western kind of death.)

All of which is a long way of saying that Sala's fans will find much of what they like on display throughout this story, and newcomers will find a fine introduction to his work.

As for the rest of the book, it contains three shorter, older black-and-white pieces.

The first, "It Will All Be Over Before You Know It ...," consists of splash pages of perfectly Sala-ient imagery — a beautiful young woman surrounded by strange characters, monster men and freighted symbolism all rendered in waves of delicately drawn black lines, with a short box of text giving each a designation of a chapter and a brief synopsis of what occurs in that chapter. The text doesn't match up with the imagery, but in looking for a connection, you'll create one.

That's followed by "Stranger Street," another series of sequential splash pages, these depicting a background character walking through a strange street crowded with strange figures without any words intruding on the imagery, and, finally, "The Prestigious Banquet to be Held in My Honor," a droll short story about the subject named in its title, one that has a dream-like nature and a bit of a twist ending.

The Musical Monsters of Turkey Hollow (Archaia/BOOM! Studios): Following the success of the previous Archaia/Jim Henson Company collaboration A Tale of Sand, the BOOM! Studios imprint adapted "the lost television special" The Musical Monsters of Turkey Hollow into a graphic novel. And to handle this particular adaptation, the publisher handed Jim Henson and Jerry Juhl's script to Roger Langridge, the cartoonist whose exemplary work on The Muppet Show Comic Book made for not only the most fruitful Muppet comics, but some of the best post-Muppet Show Muppet work of any kind.

Unlike A Tale of Sand, this project carries with it some particularly difficult challenges in terms of adaptation from television to comics, including that the title characters are Muppets and that music and sound play such an important role in the story.

That story, is this: In 1668, a rainbow meteor crashes to the Earth in what would come to be known as Turkey Hollow, apparently because everyone in town raises turkeys. The meteor is actually a sort of egg, and it hatches 300 years later, when struck by lighting. And what, exactly, did it hatch?

Seven googly, ping pong ball-eyed, fuzzy monsters, each capable of making one sound from which they take their names — Qwonck, Bowb, Shoop, etc. — sounds that, when made all at once, form a sort of symphony of scatting.

The monsters are first attracted to friendly little boy Timmy when he's practicing his guitar out in the woods. They jam with him, and then play with him. Later they befriend his sister and, when they become known to the rest of the town, get into serious trouble, due to the machinations of a mean, bitter old man who is trying to seize the land that Timmy and Ann live on with their aunt Clytemnestra.

Langridge has met and overcome the challenges peculiar to this sort of work in the past. His monsters are perfectly designed and acted by the cartoonist; they look like close relatives of the sorts of monsters that populate Sesame Street or might appear in the background of a Muppet Show skit, and they even move and act like a Muppet monster might, albeit without the need for Langridge to position them in places that always hide the humans operating them. Langridge has shown in the past he has a unique ability to essentially create Muppet performances out of paper and pen; he doesn't just draw comic book versions of Muppet characters, but draws comic book versions of television Muppets, a virtuoso sort of adaptation that translates puppetry meant for television into another medium.

The music is a bit more challenging. Sound is, of course, notoriously difficult to write or draw, and music all the more so. Langridge and colorist Ian Herring adopt a synethesic approach, using bright colo r— in contrast to the more muted, fall hues of the rest of the story — to highlight music, sometimes drawn as notes and lyrics, sometimes as swirls of color.

When Tim and Ann sing their songs on guitar — the latter is teaching the former to play — the lyrics appear in a column above them. When the music is meant to play over the action, like a soundtrack, the lyrics appear a few words at a time in big, colorful block letters. And when the monsters make their noises, forming their little vocal orchestra, their sounds are each rendered in a bright color, and crowd the panels, overlapping one another.

In 2014, it's difficult to imagine how this might have turned out had it been a TV special in the late 1960s as originally intended. Certainly there's less competition for Thanksgiving specials than for Halloween and Christmas ones, and I suppose there's every chance it could have turned out to be a classic. Regardless, Henson and Juhl have created a classic-feeling comic, thanks to the talents of their collaborator Roger Langridge.

Walt Disney's Uncle Scrooge: The Seven Cities of Gold (Fantagraphics): The latest volume of Fantagraphics' ambitious assemblage of a Carl Barks Library — the publishing initiative that I remain more excited about than any other — is fuller than most with the sort of grand, epic adventure stories for which Barks and his work on the Disney duck comics are most famous for.

The title story comes from the first in the collection, in which Scrooge McDuck laments that he's so successful and owns so many businesses that he can't even think of a new field to go into. Just then his nephew Donald and grand-nephews Huey, Dewey and Louie drive by and announce they're going arrowhead hunting. Learning that he doesn't own "any companies that go around looking for Indian arrowheads," Scrooge joins them ... and the ducks eventually find clues that lead them to the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola, with the Beagle Boys hot on their tails.

Scrooge and his nephews seek other mythological treasures in the form of the Philosopher's Stone and the Golden Fleece (both of which they find, but which prove to be more trouble than they're worth), get involved with a pair of unusual races (a steamboat race and a fastest-animal-in-Duckburg race), chase a lemming across the Atlantic Ocean and then back into it and, in the weirdest of the stories included herein, find themselves an a mysterious island where objects are regularly petrified.

As is always the case, these longer adventure stories are balanced out by shorter stories, some of which are simple one-page gags (most of which revolve around Scrooge's extreme frugality) and other one-joke strips that go on for several pages.

Of all the great comics collected in Seven Cities, "Riches, Riches Everywhere" might not be the funniest or most exciting, but it's the one with the clearest moral regarding what's important in life. Intent on proving himself the greatest prospector, Scrooge chooses a spot on the globe at random — the Australian Outback -- and drags his nephews there. True to his word, Scrooge immediately finds a valuable mineral deposit. And then another. And another.

But when circumstances turn dire, and Scrooge and Donald find themselves wandering the desert without supplies, Scrooge can't find the one thing they need more than any other: water. Even when he hears a burbling, liquid sound and the ducks use their remaining strength to get at it, they're greeted not with a hidden spring, but a gusher of oil.

Whether this is the seventh volume of Fantagraphics' Carl Barks library you read, or your first, you're going to like, if not love it. Because if you like comics, you like Carl Barks, whether you know it yet or not.

Wonder Woman Vol. 5: Flesh (DC): It's been evident for a long time now that writer Brian Azzarello was only really interested in telling a single Wonder Woman story, albeit a very long one. That became abundantly clear recently, as he and his primary artistic collaborator Cliff Chiang just finished up their 35-issue run on the series. Some writers are accused of writing for the trade, but here Azzarello seems to have been writing for the omnibus.

Azzarello, Chiang and company's run was devoted to a war of succession among the Olympians, as Apollo/Sun claimed his dead father Zeus' throne, and began battling against members of his family, trying to defend his new place of power from a pair of prophesied usurpers — a baby recently born to mortal woman and The First Born, a savage, seemingly unstoppable god that pre-dated Greek mythology. Wonder Woman became drawn into the conflict not simply to protect the baby and its mother, but because of an "Everything you know is wrong!"-style retcon of her origin: Apparently, she's really the daughter of Zeus.

In this penultimate collection of the run, it's basically more of the same, as Wonder Woman and her allies — including the rather out-of-place Orion of the New Gods — battle against the squabbling Olympians, the First Born and the First Born's followers, with ever-shifting alliances shifting further, as friends-turned-enemies of Wonder Woman's become her friends again, and former enemies side with her.

Like the single issues, the collections of Wonder Woman can read a little repetitive, given Azzarello's approach to the material. It's the same cast and the same handful of settings, all fighting a never-changing conflict, giving the comic something of the claustrophobic feel of a television series – a feeling that is no doubt exacerbated by the supposed cosmic significance of the characters and their lives.

It's not a bad way to write a comic, but it's not exactly a fun comic book to read ... at least, not serially. Once the final collection is published, and a reader can read Azarello and company's Wonder Woman from start to finish in a sitting or two or three, it will likely take on the epic grandeur that it seems to always be feinting toward, but is never really able to build up the necessary momentum needed to achieve, given the one-month break every 20 pages (or six-month break every 100-120 pages, if you're reading it in trade).

The artwork is still primarily by Chiang, quite an achievement given the tumultuous turnover of so many of the New 52 titles, and Goran Sudzuka, Aco and Jose Maran Jr., who do a fairly incredible job of attuning their styles to Chiang's so that even when he isn't drawing a passage of Wonder Woman, it's quite easy to forget that he isn't.