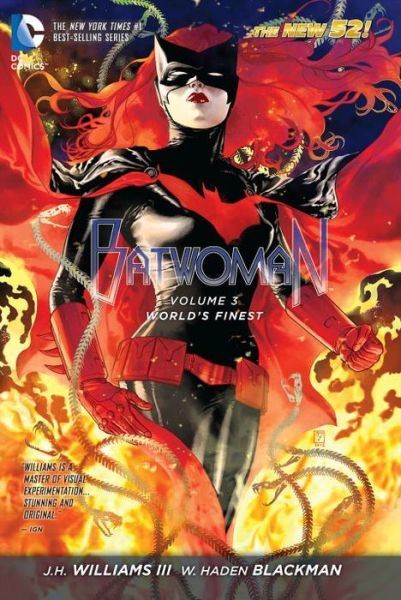

Batwoman Vol. 3: World's Finest (DC Comics): It's difficult to talk about this comic without also discussing the announced departure of its creative team which, like several others that have worked on DC's New 52, left amid quite public complaints of editorial interference.

As an auteur-driven book starring a relatively new character that's barely been drawn by anyone other than artist and co-writer J.H. Williams III, the whole affair strikes me as strange, as Williams seems to be at least as big a factor in the book's continued existence as the word "Bat" in its title. And it's stranger still he and co-writer W. Haden Blackman are only now reaching the breaking point, as from a reader's perspective, DC appeared to have pretty much left them alone to do their own thing; like Grant Morrison's Batman Incorporated and the Geoff Johns-written portions of Green Lantern, this book seems set in its own universe and is sort of impossible to integrate into the New 52 if one thinks about it for too long (with "too long" being "about 45 seconds").

Regularly cited as one of the best of DC's current crop of comics, Batwoman is definitely the company's best-looking, and most intricately, even baroquely designed and illustrated. As for the word half of the story equation, I found Batwoman — and this volume in particular — to be extremely strange, even weird, more than I found it to be good.

Blackman and Williams take a novelistic approach to the story, with almost every character getting a great deal of attention, and multiple heroines narrating their own conflicts throughout. I'm unsure how it read serially, but collected, it's like a graphic novel in the truest, most direct, most literal sense of that term.

Now, most of the goings on are fairly generic crime-fiction stuff, with urban-fantasy elements laid on top. In this volume, Batwoman teams up with Wonder Woman (who, interestingly enough, seems like a third version, distinct in character from both the one in Wonder Woman and the one in Justice League), and Batwoman's urban legend enemies are shown to share some space with characters from classical myth.

It's heady stuff for what remains, at its heart, just another fight comic. But with such an exquisite body built around that heart, it's easy to ignore the book's failings when there's so much eye candy, so many brilliant bits of design and clever page constructions to distract the reader.

Despite its many apparent attributes and its many, many flaws, Williams and Blackman's Batwoman comics are unlike anything else DC or their traditional rivals are publishing, and that unusualness is argument enough for its continued existence. Ah, well. About half of the characters in this are original creations or public domain characters, and, ultimately, I suspect Batwoman needs Williams more than Williams needs Batwoman.

(Confidential to Bette Kane: With "Hawkfire," I think you managed to find the only superhero codename more lame than "Flamebird.")

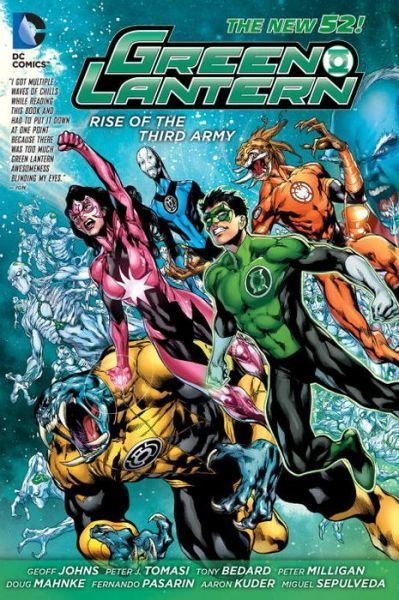

Green Lantern Lantern: Rise of the Third Army (DC Comics): This massive, 400-page hardcover collects all of the Green Lantern franchise comics branded with the "Rise of The Third Army" logo, which means four issues each of all four of the Lantern books, plus a couple of annuals.

If you followed this crossover as it was published serially, then you already know it wasn't exactly an 18-part storyline where every issue was mandatory reading; with the exception of the kick-off and conclusion, all four titles had their own little storylines, a fact emphasized by their grouping here by title, rather than the order they were published. It's a bit like the old triangle-numbering of the Superman books in the 1990s; technically it's all one big story, but each book could focus on its own cast and corner when desired.

This is the penultimate chapter of Geoff Johns' nearly decade-long run on the character, in which The Guardians finally go irredeemably too far, creating a replacement army to their Green Lantern Corps, an army that is essentially a zombie plague spread by touch; it seeks to convert every sentient being in the universe into scary-looking, bug-eyed, mouth-less monster men with visible green brains.

Four mini-arcs check in on the four casts of the four books to see what they're up to during all this craziness, before all of the heroes unite to save the day. The Johns/Doug Mahnke bits following newly minted human Lantern Simon Baz were the only ones I found too terribly compelling, and they were by far the most visually compelling (but there's some nice art here and there throughout, like a bit by up-and-coming DC Comics superstar Aaron Kuder). The packaging of the entire franchise between covers like this does provide a nice way to sample its state, and the particular flavors of the various books, whether or not you end up liking themt. In grocery terms, this is a variety pack, and one you can buy in bulk.

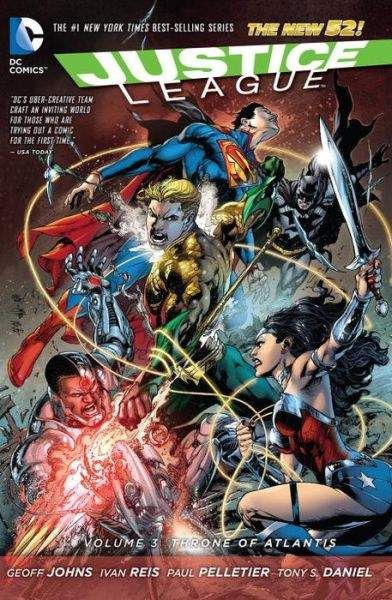

Justice League Vol. 3: Throne of Atlantis (DC Comics): The Geoff Johns-written, rebooted Justice League title finally starts to feel like an actual Justice League comic by the time the title story begins — which is Issue 15, if you're curious. By that point, the focus shifts dramatically from the many New 52-premised changes in the team's history and roster, and falls instead on the core idea of DC's most iconic heroes uniting to fight an incredible threat.

Here that threat is an invasion from Atlantis, led by Aquaman's younger brother Orm, aka Ocean Master. The story was actually split between issues of Justice League and the Johns-written Aquaman, with Ivan Reis penciling the Justice League issues and Paul Pelletier the Aquaman issues, the latter modulating his style slightly so that it syncs up incredibly well with that of Reis. Reis was the fifth pencil artist to work on the book's lead feature in that relatively short time, but he was also the all-around strongest in terms of storytelling, as these issues evidence.

Plot-wise, there's a Marvel feel to the "Atlantis Attacks!" story, with Aquaman and Ocean Master both scanning like Namor in different moods (in fact, Johns' Aquaman bears a greater resemblance to Namor than past iterations of Aquaman). The writer slims down the lineup by having Green Lantern leave the team and keeping Flash busy elsewhere, which has the effect of presenting the heroes with even more overwhelming odds — given a palpable scale by Reis and Pelletier in a way that, say, Jim Lee's splash pages of Parademons in the first arc lacked — and providing an excuse for a calling-all-capes cry for help near the climax.

"Throne" is preceded by the two-issue "Secret of The Cheetah" story, drawn by Tony Daniel, which focuses mostly on Superman and Wonder Woman's budding romantic relationship, and the current origin of the Wonder Woman foe, which most closely resembles George Perez's version of her.

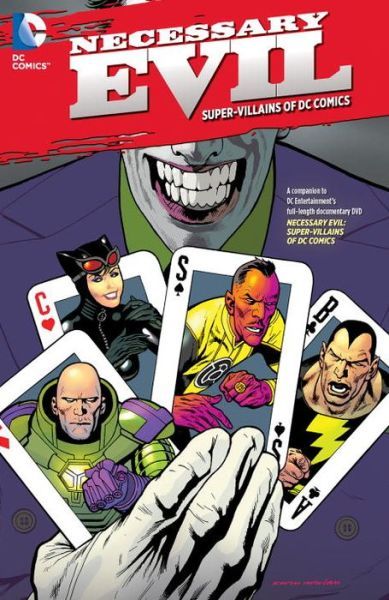

Necessary Evil: Super-Villains of DC Comics (DC Comics): A little-heralded, or even noted, aspect of DC's Villains Month, given the attention the goofy 3D covers attracted in September, this trade paperback bills itself as a "A Companion to DC Entertainment's Full-Length Documentary DVD" of the same title. I haven't seen it, but it's a DC documentary about DC's villains, which sounds like it may veer closer to infomercial territory. But hey, they got Christopher Lee to narrate it, so it's gotta be at least worth a little attention; I'd stay up late to watch paid-advertisement programming of Christopher Lee selling kitchen gadgets, miracle cures, Girls Gone Wild DVDs, gold investments, commemorative coins, whatever.

As for the contents of the comic, they are comprised mostly of the short, two-page origin stories Scott Beatty wrote for the backs pages of Countdown. Those included here are (deep breath) Lex Luthor, Doomsday, Bizarro, Sinestro, Gorilla Grodd, Black Manta, Poison Ivy, The Riddler, The Penguin, The Scarecrow, Harley Quinn, Bane, Mr. Freeze, Solomon Grundy, Deathstroke and Darkseid, by artists Andy Clarke, Jon Bogdanove, Doug Mahnke, Fernando Pasarin, Arthur Adams, Mike Norton, Stephane Roux, Don Kramer, Scott McDaniel, Bruce Timm, Graham Nolan, Thomas Derenick, Tom Mandrake, Tony Daniel and Ryan Sook (plus a Two-Face origin by Marks Waid and Chiarello). That right there is an awful lot of great artwork from some great artists.

The remainder of the book is a grab bag of short-ish stories by a variety of creators, including one classic (a 1972 Ra's al Ghul tale by Denny O'Neil, Neal Adams and Dick Giordano), a few very short, interesting-for-their-art pieces (Tim Sale and Darwyn Cooke's Batman "Versus" Catwoman story from the Sale issue of Solo, and a Clayface II story drawn by Mike Mignola and Kevin Nowlan) and a somewhat-random sampling seemingly chosen for the popularity of their creators and/or the fact that the characters are apparent favorites of DC editorial (a Jeph Loeb/Tony Harris Luthor story, a Geoff Johns/Richard Donner/Rags Morales Phantom Zone criminals story, a Dave Gibbons/Patrick Gleason Sinestro story, an issue of Loeb and Jim Lee's "Hush" arc featuring The Joker, an issue of Peter Tomasi and Doug Manhke's 2008 Black Adam series).

It's not a bad sampler of DC talent and characters, but it's immediately and unavoidably striking that everything in here is pre-New 52, and the content of almost every single page of this thing has "expired" in terms of narrative relevance. The Luthor piece, for example, is set during his successful 2000 run for the presidency, there's a Cheetah/Reverse Flash team-up featuring the old version of The Reverse Flash and the no-longer-extant Wally West and so on.

From costumes to events to the "Essential Storylines" suggested at the end of each two-page origin, this might have been a great way to introduce new readers to the DC Comics of 2008 or so, but now looks like a weird artifact of a happier time when DC could and would hire creators of the caliber of many of those mentioned above, and they had enough of a handle on their own continuity that they could stitch together comprehensible histories for their villains and their origins.

Pompeii (PictureBox): In a rather tried-and-true formula of historical tragedy dramas, the readers will all know exactly what happens to the ancient Roman city built in the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, but the characters have no idea. From the first page, then, cartoonist Frank Santoro's narrative is fairly packed with apocalyptic tension (I believe it was Anton Chekov who wrote that if there is a volcano on the stage in the first chapter, it must erupt by the last chapter), a threat of a localized apocalypse that's so inevitable it simultaneously renders the lives and conflicts of the characters both ultra-urgent and ultimately trivial.

These lives and conflicts belong to Marcus, a young man from a small town who has come to Pompeii to apprentice himself to a great artist; Flavius, the great artist; Lucia, Marcus' lover who has followed him to the city and is now having second thoughts; Alba, Flavius' wife; and the Princess, a young, beautiful woman Flavius is painting a portrait of and also having an affair with.

Marcus' job includes not only mixing paints for Flavius and helping him fill in backgrounds, but also running interference for him to help uncomplicate his love life. His own life is complicated by Lucia's desire to perhaps have a child, and/or someday move back to their hometown, creating a tension for the young artist between his dream of creative glory and romantic contentment.

Not that any of that much matters, what with the volcano and all.

Santoro's artwork is stunning in its simplicity and the degree to which it serves the story. Working in only a brown crayon over a creamy white paper (with a handful of scenes seemingly done in a water color), he creates characters with the faces and features of those of Classical-era artwork, while the panels and pages they occupy have a confidently sketched style reminiscent of that of a storyboard or the layout for a comic that will be more fully rendered later (in several instances, he even draws arrows to indicate motions like turning, as one would find in an animation storyboard).

Like the work and life of young Marcus, it seems to have been interrupted before a final, more fussed-over version could be completed. And yet there's a sad, elegant beauty to it just as it is, with an external force deciding when a work is done, whether that force is an act of nature or God, or the will of the artist himself, making a stylistic decision.

School Spirits (PictureBox): Can I talk about me for a moment? Of the many things I miss about my youth, one of the most particular but difficult to articulate is the way my imagination used to work. I guess you could call it daydreaming of a sort, when one finds one's body stuck in one place for a long time — say, school — and one's mind drifting into a sort of long-form imagination meditation that, for me, usually involved sketching and doodling on handouts and in the margins of my notebook.

I've never really been able to recapture that way of thinking, perhaps because when one becomes an adult one has more control of one's life, and can work to avoid the sorts of boring situations that lead to that sort of daydreaming. Or perhaps that's the difference between a hormone-addled teenage brain and a content yet cynical adult brain.

Cartoonist Anya Davidson, on the other hand, not only remembers that sort of stream-of-conscious, lucid daydreaming, she's managed to capture and convey it in her debut graphic novel.

It's essentially a series of short subjects starring misfit high-schooler Oola and her similarly misfit friends, and she regularly slips into long, even epic, flights of fancy that occupy just about as much page-space as the events of the stories .

For example, in the first section, Oola and her friend Garf listen to the new Hrothgar album at the record store, and Oola finds herself transported to the seventh dimension, where Hrothgar himself lives, and he offers her guru-like instructions on living one's life.

In the next story, "Battle for the Atoll," a two-page field trip to a museum by the teens is preceded by a 24-page, silent story of an epic battle involving a vaguely Kirby-esque space culture, an all-female island culture and a war with white, male European powers, all leading to an explanation of how one of the pieces got into the museum -- which Oola and Garf ignore to fool around and sneak out for a smoke.

Later, when Oola's breast rubs against her bra funny in class, she gets really horny and looks at a male classmate, thinking "Oh, Grover, you'd be sick if you knew what all I'd like to do to you!" That leads to 42 examples of what she'd like to do to him, much of which is sexual, and a little of which is romantic, but most of which is just weird, including panels of her head on a giant dog that Grover is walking, or her shooting him out of a cannon, or dropping money on him from an airplane, or making his head explode through the power of thought.

That's the basic gist of the comic; a sort of sexy, punk rock, teenage rebel girl version of "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty."

Davidson's artwork is a little difficult to describe: Her layouts are pretty straightforward grids; consisting of small-ish panels with a regular, even rigid, patterns (the aforementioned sex fantasies occur on a series of nine-panel pages, for example). The art within them is wild and weird. She uses a lot of very heavy blacks on the white of the page, with crosshatching accounting for the only shading. Her designs are somewhat cartoony, but not in a way that evokes animation; instead, her design sense seems more informed from classic comic strips filtered through underground comix and 'zines, and the stuff she puts in those panels can probably best be described as some seriously weird shit.

Davis apparently refers to the work as "Beavis and Butt-Head meets James Joyce's Ulysses," and while I think it falls decidedly between the two without having a whole lot in common with either, it does favor a little-seen comics equivalent of the narrative strategies of Joyce's prose. At least, I think so; I wasn't really paying attention in class when we talked about Ulysses in my college English classes.

Sickness Unto Death Part 1 (Vertical): Writer Hikari Asada and artist Takahiro Seguichi open their book with their psychologist hero Futaba at the grave of his lost love Emiru, who he tells his companion he failed to save. When he begins to tell the story and the narrative flashes back, one might think seeing where it ultimately ended would drain it of suspense, but that's hardly the case, given all the mystery that exists between points A and B.

Futaba comes to town to attend college, planning to study psychology and try to address the suffering caused by mental illness. Upon his arrival, he meets a frail young woman having a panic attack, and saves her, only to discover she owns the boarding house where he'll be staying (along with the other two occupants of the sprawling mansion, an elderly butler and a young invalid mistress).

She's suffering from an array of mental problems that are so bad they take an incredible physical toll, but her central problem is that of despair, specifically living has become so intolerable that she wishes she could escape it through death, but she knows she cannot die — that's where the title comes from, via Soren Kierkegaard (Along with Flowers of Evil, this makes for a second Vertical-published manga that takes its title and inspiration from a work of a European writer).

Also, there's a ghost involved, although it remains to be seen if that ghost is real or part of the catalog of mental problems afflicting Emiru. The first half of a two-part series, this is a spooky and unsettling melodrama, precisely because it deals with something as terrifying and terrifyingly real as mental illness, here exacerbated by teenage lust and longing and the helplessness of youth in the face of adult problems.