After eight seasons and a made-for-TV movie, veteran writer/producer Joel Surnow is tired of 24 – not the series he co-created, but the hours, the day-in, day-out schedule that accompanies television production. That’s why his latest project is just 95 minutes long, and takes place over the course of an entire summer: Small Time, a lighthearted drama starring Christopher Meloni as a salesman trying to reconnect with his son after hiring him on at his used-car lot.

Based on an idea he conceived in the 1970s, the film marks Surnow’s feature directorial debut, and introduces a phase of his career he hopes will take him away from the “young man’s game” of television that previously gave him so much success.

Surnow recently spoke with Spinoff Online about Small Time, and the process of updating it from its ‘70s origins to today. In addition to talking about how his own changing perspective changed his approach to the material, he discussed making the transition into smaller, more intimate passion projects, and offered insights into the upcoming Fox miniseries 24: Live Another Day – in particular, what he thinks it needs to have, even if he’s not interested in personally making sure it has it.

Spinoff Online: You’ve talked about how this was very different when you first conceived it, and that you had initially told the story from the point of view of the kid. How did you decide to make it ultimately about the father?

Joel Surnow: In the first draft, the first script in 1976, the kid was barely in it. It was about these two guys and their business is going under. They’re going to move to Miami and then he ends up getting back together with his ex-wife and the partner. It was really more about what’s going to happen between Martini [played by Breaking Bad’s Dean Norris] and Klein [Meloni]. So after I wrote it I went and worked for my dad. I actually had that experience of working for my dad. So when I started thinking about what’s the right story for this I started thinking I’m going to make it a father-son story. And it just – it was born out of my experiences working for my dad and all that. So the most emotional and kind of fresh idea would be to have a story about a kid who doesn’t want to go to college and work for his dad sort of like I did when I worked for my dad and his partner. So that’s where it started, but if you’ve seen the movie you see there’s a lot of different stuff going on. There’s a relationship between a guy and his ex-wife and resolving that. And kind of you see him crying at the beginning of the movie – he doesn’t even know why he’s crying. He’s a guy kind of out of touch with a lot of stuff and it takes him a while to kind of put it all together and it’s kind of painful along the way. So the movie’s sort of evolved out of the father-son relationship. If you were to look at this as a three act piece, the end of act one identifies the movie as the kid saying I want to come work for you.

The movie offers, I think, a pretty accurate, unflattering portrait of like teenage know-it-all-ism, and the movie is definitely more sympathetic to the father character even though he’s dealing with all these different things. Do you feel like it’s a product of maybe changing perspectives from the time when you wrote this to the time when you made it?

That’s a good point. No, that’s interesting. I do, because this perspective when I wrote this at 21 years old was, like, my dad and his partner were these really cool guys. And they were kind of Rat Pack-y in the first script. They didn’t have a lot of depth, you know. I was in my 50s when I rewrote it, and I had been through a divorce and I had kids that I had to see every other weekend – so there’s a lot of pain in Klein’s life in the rewrite that wasn’t there at the beginning. It was more of a kind of a fun-loving romp at the beginning, and now I turned it into a real family drama. But I wrapped it in this kind of comic upbeat works of two salesmen, and I cast it with kind of fun guys. And it’s sort of a Trojan horse a little bit. You think you’re kind of watching a fun movie and then all of a sudden it hits you between the eyes and you realize, “Oh, God, there’s some dark stuff but, you know, painful stuff going on.” Deeply felt stuff. And that – if the movie succeeds it will succeed because of that. It’ll succeed because of the relationship between Chris and Devon.

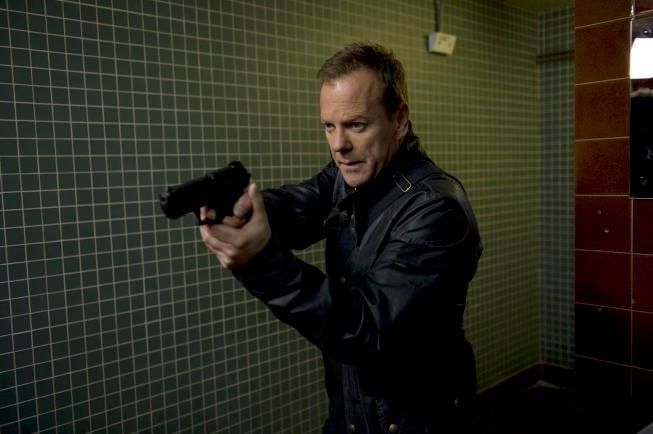

Christopher Meloni is "Small Time" on the Big Screen

What’s interesting about the movie is that the defining characteristic of the relationship between Chris and his son is that there is a distance to it. Chris’ character doesn’t go up and talk to him when he’s at school, for example. What do you take away from that in terms of what might more conventionally be perceived as a healthy relationship?

I don’t know if there’s a distance in it as much as he had to grow up accepting the fact that he wasn’t going to be a full-time dad, that he really wasn’t going to be raising his kid. His wife and her husband had the kid every day. And what he really wanted was what was best for the kid. So when the kid comments and says, “I want to come work for you,” it’s sort of the set-up punch. But the knock-out punch is, “I want to come live with you and make up for lost time.” That’s irresistible to him. And then what happens in the movie is it doesn’t work the way it’s -- he wanted it to and at the end he does something that he’s never done before. He sacrifices what he wants himself, not involuntarily but voluntarily for the good of the kid. And so I think that scene when he goes to see the kid and doesn’t go is just like he’s in a good place. I’m not going to disrupt that. Let him – he seems happy and I’m going to, you know, continue with my sacrifice. And I think that’s sort of – it’s not distance. I think there’s a lot of love there and I think when you see the kid there at the end he’s directing the commercials it’s come full circle. It’s now more of a natural relationship. But people who are kids of divorce – and that’s sort of what my next movie that I hope to be making is about, it’s an unnatural kind of parenting when you don’t see your kid all the time. Things you take for granted when you live with your parents suddenly become different when you see them every other week, you know. And that’s a subtext that isn’t ever explicit in the movie but it’s implied.

One of the problems that sort of smaller movies face is sort of finding a scale that resonates with people. How do you find the right scale when you’re doing something that is self-contained like this, that’s realistic without being boring or compelling without being melodramatic?

Well I think everything has its own size, you know. Small Time. I mean, the title itself describes the fact that there’s nothing pretentious or big or flashy about it. But what I feel is important and I think has come – certain movies or TV shows become a little nihilistic where the heroes are so anti-hero that I’m not even quite sure what I’m supposed to care about. And I guess I come from an old fashioned place but I like to like my characters. Or if I don’t like them, I like to at least admire them, you know. I don’t know if Jack Bauer’s the guy you want to hang out with because he’s so intense. But you admire him and you want him to succeed because he’s on the side of the angels. These guys you like but you need to make it important enough that they do something that makes them – makes you love them, you know. And I think Klein does that. He sacrifices himself for the betterment of his kid. And he puts everything, you know, all his unresolved issues, I mean, he’s got a scene with his wife where he makes the right decision. He doesn’t make the easy decision. The, you know, the cynical decision. We’re so used to a certain amount of cynicism. I don’t know of this movie is going to be too positive for people because we’re used to seeing a lot of dark stuff now. And people like dark stuff but I still – I always thing that there’s something nice about having people you root for, in a very simple way.

I know you were only an adviser on the upcoming season of 24. But sort of standing on the outside of it, do you prefer now that they are taking this property and going in a different direction? Do you want it to be different from yours?

Yeah, it should stay current with the world. I mean, I don’t think it should just be a rehash. I think part of what 24 was was original. There was originality to the show the way it was shot, the way it was edited, the way it was formatted. So the more they could push it into new territory the happier I would be, without losing the core elements of it.

When I interviewed John Moore when the last Die Hard movie came out, I asked him what he thought were the essential characteristics of Die Hard and his answer was much different than I expected. I thought it was about a normal guy in extraordinary but contained circumstances, but that didn’t seem to be what he thought it was.

What did he think it was?

I don’t remember now, honestly.

It was a weird answer?

Yeah, it was a weird answer that I was a little surprised by.

The writer probably would say what you said.

Well, what would you say are the essential characteristics of 24 that you think need to be in place at least at a rudimentary level?

Jack has to be the hero. Jack has to save the day and run against the clock. Apart from that, all bets are off. You can’t turn Jack into a bad guy. I mean, we turned him into a junkie and we turned him into a guy that might have been a traitor, but he never was. I think there needs to be a price that’s always paid in the movie. It’s not a feel-good show, but you weirdly feel satisfied. But I don’t know. I think 24, if I was the head of the networks, would be a Law & Order. It’s a great format and it doesn’t have to go that grand. I mean SVU was different than Law & Order but it was still Law & Order, you know. It still felt roughly like in the same ballpark. It wasn’t a half-and-half show like Law & Order but it still was New York and the streets and tough cops and stuff like that. I think 24 has the same thing. If you have enough of the elements that format should just be able to play forever on television.

You mentioned that your next project is about a family going through divorce.

No, it’s a father-daughter relationship over 25 years.

How do you structure something like that?

I wrote it as a six-hour miniseries and brought it down to a two-hour movie. That’s what I did. That’s how I structured that.

That seems pretty easy.

Oh, yeah, real easy. That’s called the dumb way to do it.

Does that require you to think logistically about how to create a character that’s cohesive throughout that time period?

No, I think in a way it was an exercise of getting to know who the characters were and doing it. And then I sharpened it up. I hope to be shooting it by this summer but, you know, it’s a lot of hurdles have to be crossed before I get there.

You’ve talked about how television in a way is a young man’s game. Do you ever feel that tug when you’re, say, advising these guys on 24, going, man I wish I could get in there!

No.

No?

No, I had a wonderful run in television and I feel like I graduated high school; I don’t really want to go back to high school. But I had a great run at it. And one day I may want to do something with work on TV, but I’m really much happier doing these smaller personal projects now. The thing is finding the business models that make that work, because they’re hard. People understand why you should try and create a hit TV show because it’s international and it’s huge. It’s a little less clear why you should make a small movie, you know, from an investing point of view.

Small Time is playing now in select theaters.