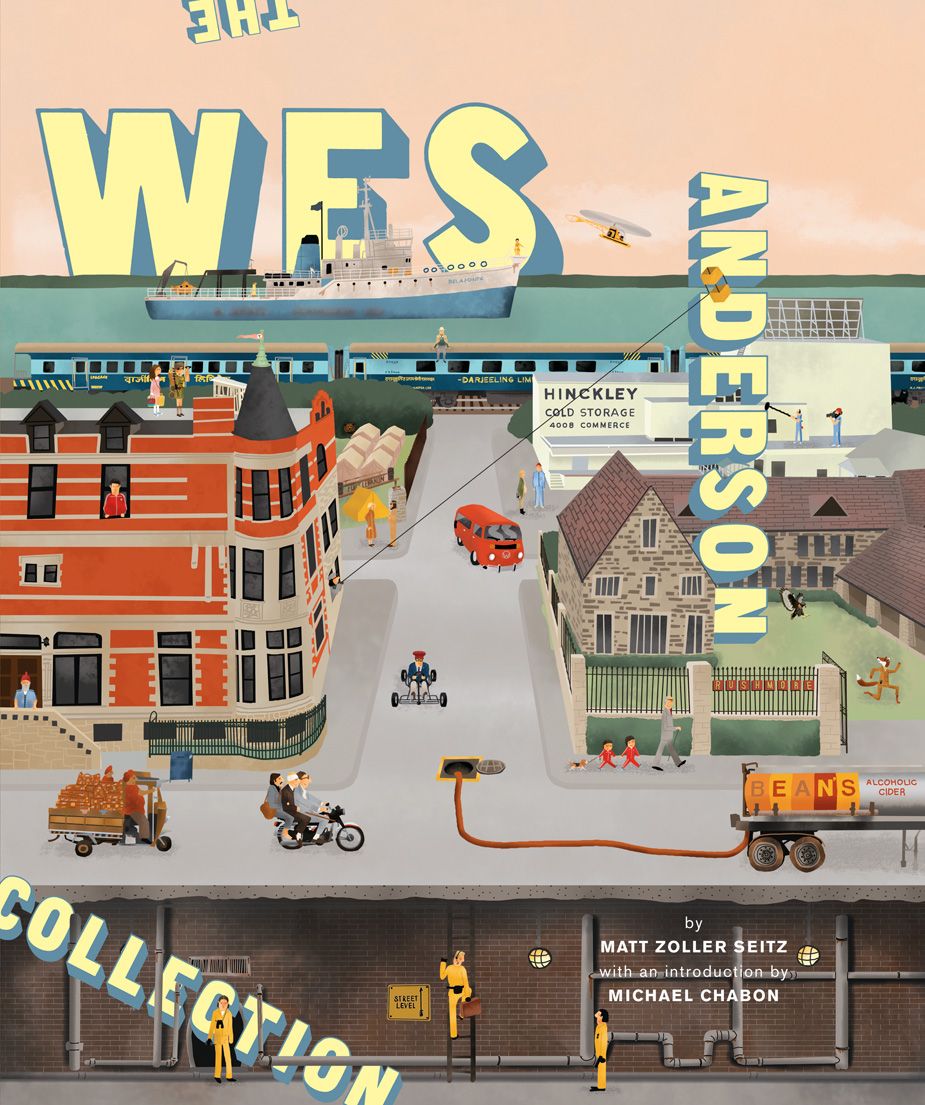

The Wes Anderson Collection isn’t a cheap book – $40 U.S. – so the odds are the only people who’ll buy it are moviegoers already obsessed with the filmmaker. Having said that, anyone who reads the book will likely become an intense, obsessive viewer of Anderson films.

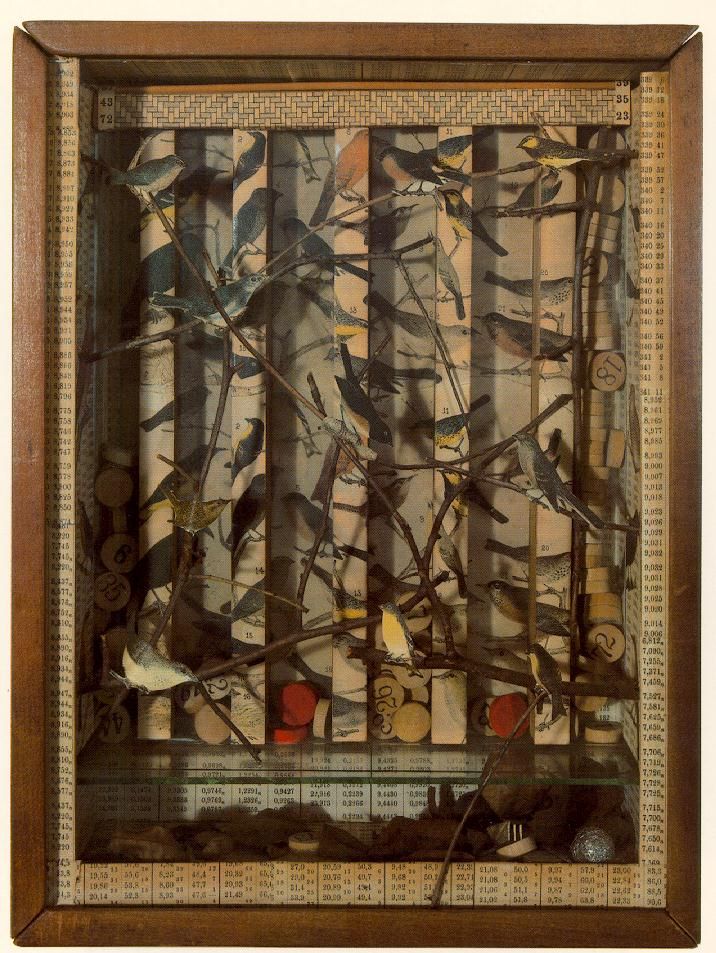

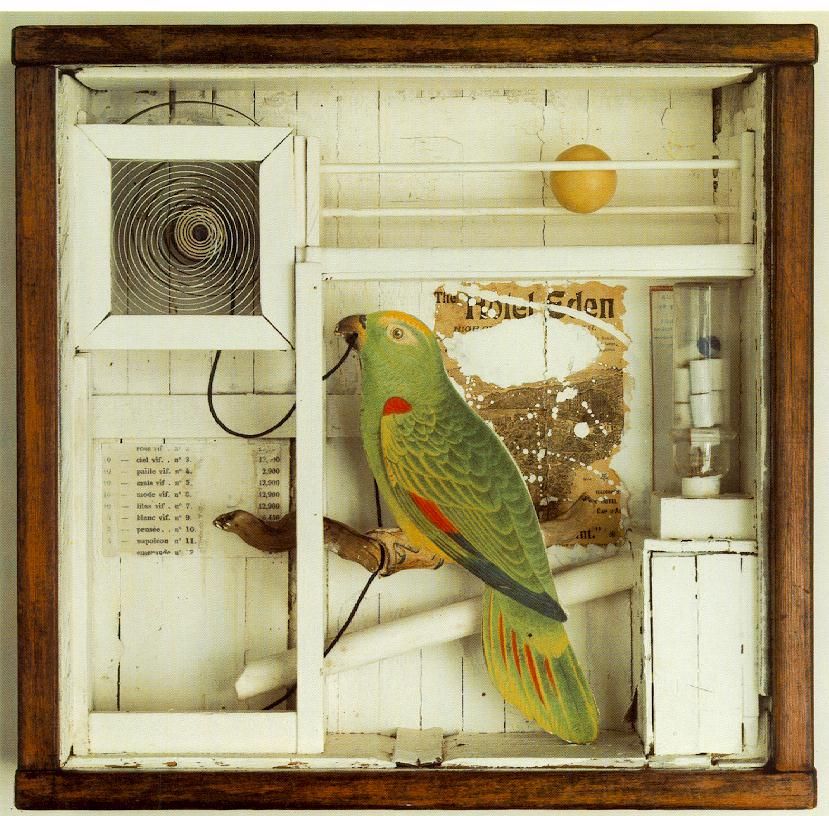

There’s an introduction by Michael Chabon that doesn’t add much, but the Pulitzer Prize-winning author compares Anderson’s work to that of Joseph Cornell, the noted visual artist best known for his assemblages that became known as “Cornell boxes.” It was about the objects in the box, how they were arranged in relationship to one another, and above all, the box itself. (Side note: Cornell made a cameo in Chabon’s 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.).

The heart of the book is a series of long interviews between Anderon and author Matt Zoller Seitz, a shameless Anderson fanboy. He claims he was the first professional film critic to write about Anderson (he reviewed the short film Bottle Rocket 20 years ago) and actually screamed out “that’s my house” at a screening of The Royal Tenenbaums). Like elements in a lot of Anderson films, such a statement could be too cute and end up annoying, or it could help build enthusiasm. It does the latter.

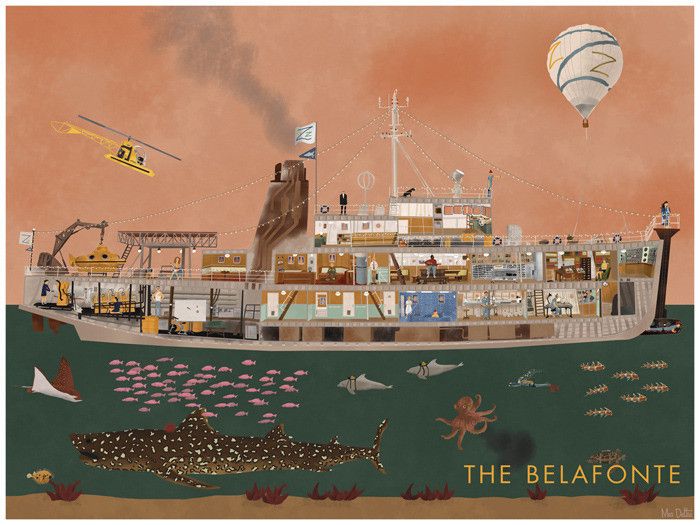

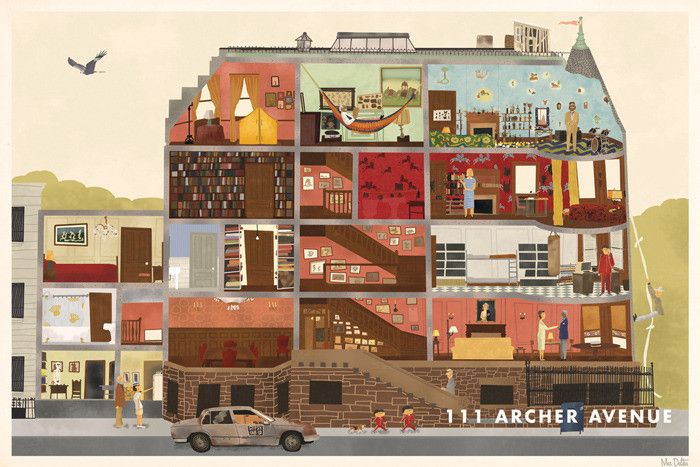

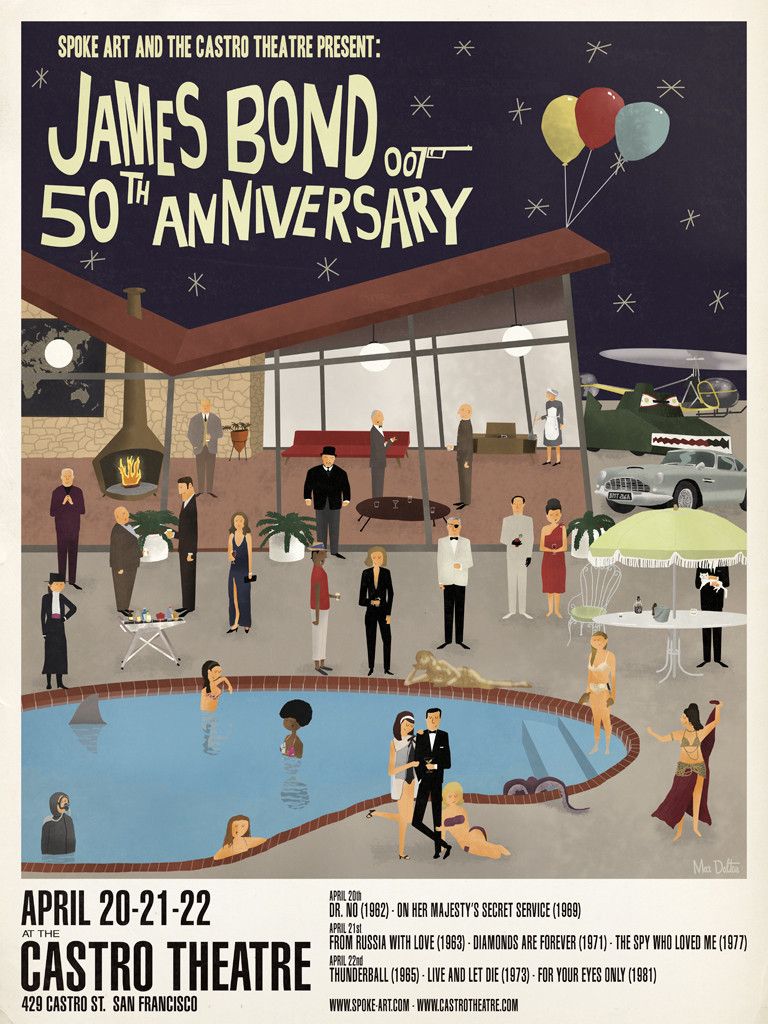

Max Dalton deserves a great deal of credit: He illustrated the cover, and he contributes multiple pieces throughout the book, including large two-page spreads for each movie.

If Dalton’s work looks familiar, you may have come across him at Spoke Art Gallery in San Francisco, or through the work he did for the Castro Theatre, also in San Francisco.

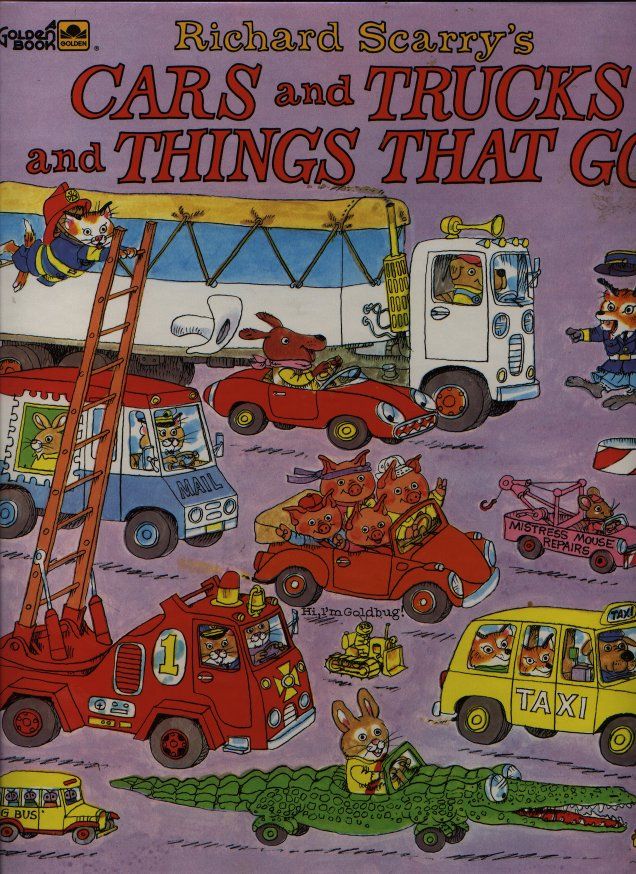

Dalton’s work is precise, detailed, colorful and beautiful. In this, his work can be compared to Anderson’s; I couldn’t help but think of Richard Scarry’s old picture books.

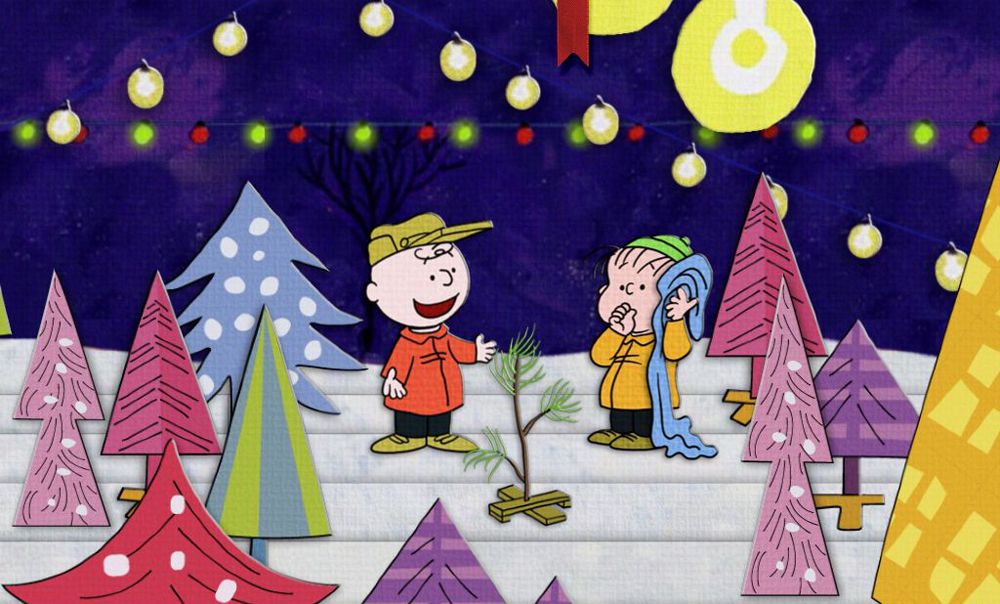

It shouldn’t be a surprise to viewers, but Anderson loves Peanuts. He’s a fan of both the Charles Schulz strip and the television specials, particularly A Charlie Brown Christmas, and wanted to use the Vince Guaraldi music.

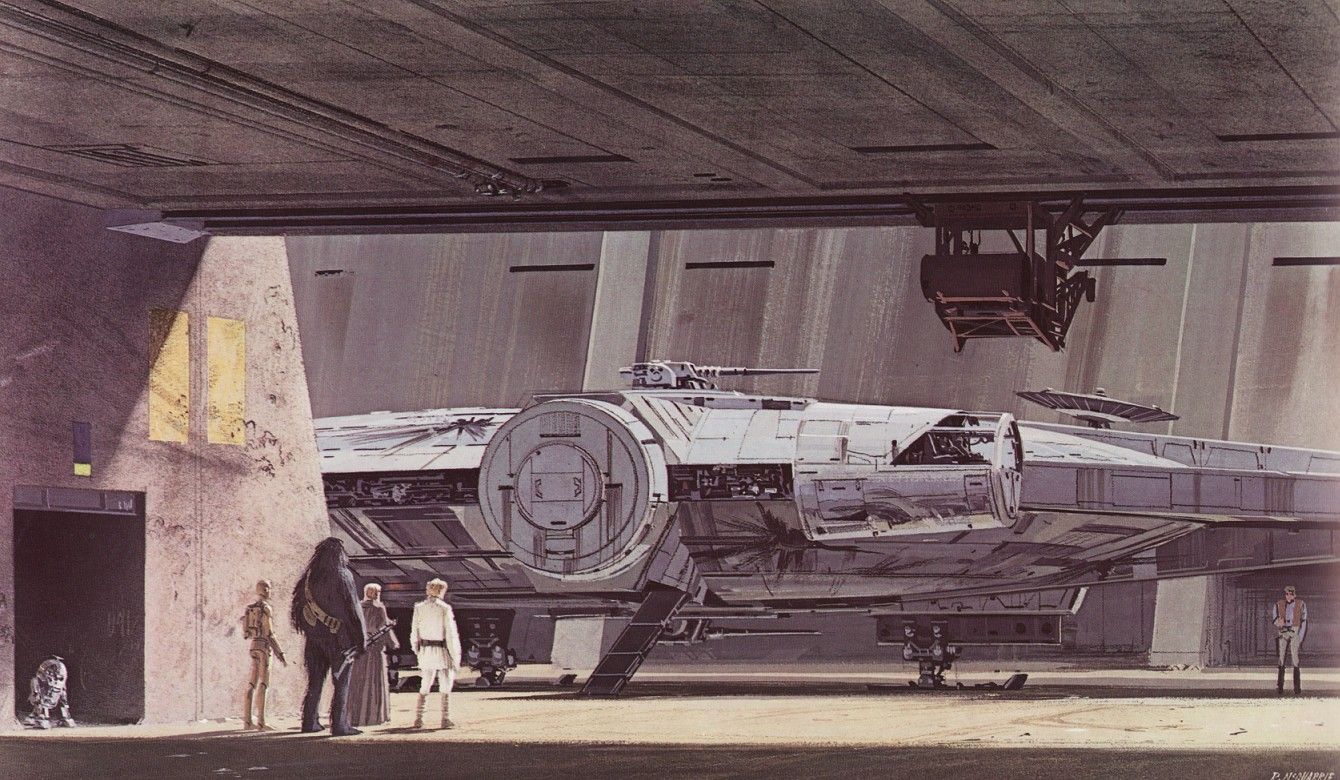

Another of Anderson’s great loves – like many people of his generation – is Star Wars, and he obsessed over The Art of Star Wars, which largely consisted of Ralph McQuarrie’s design work.

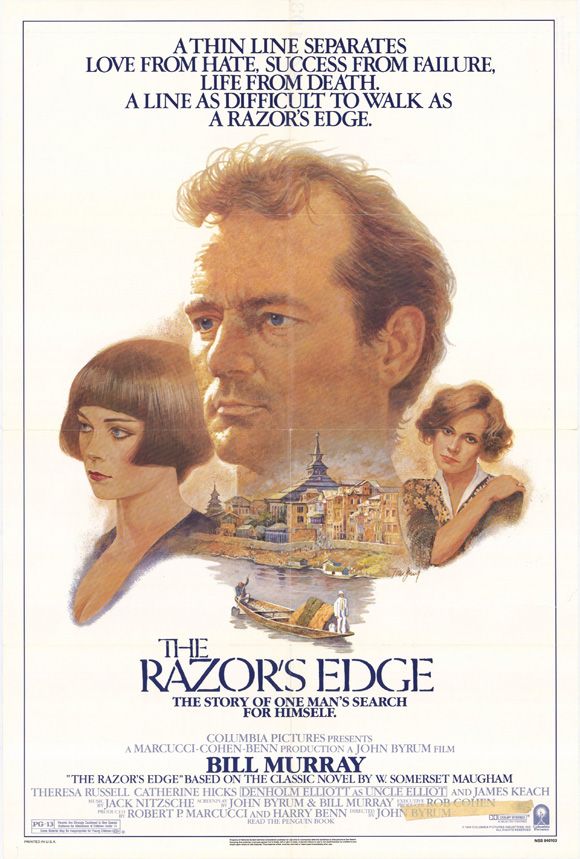

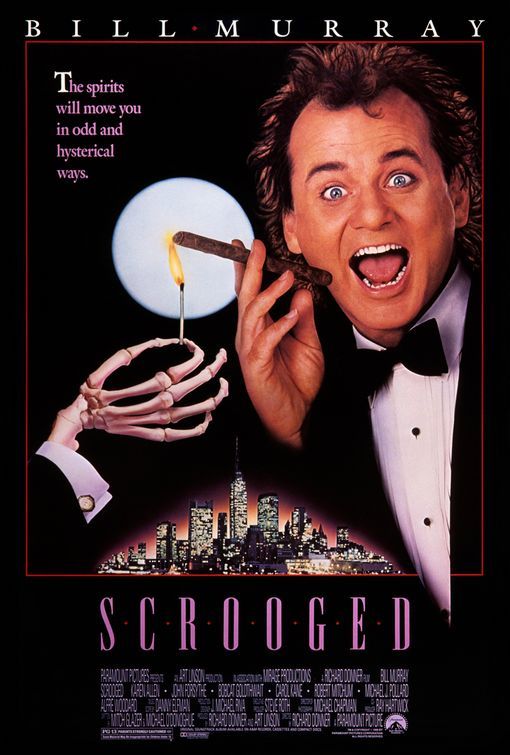

When asked why he wanted to cast Bill Murray in 1998’s Rushmore, Anderson cites four films: Mad Dog and Glory, Ed Wood, The Razor’s Edge and Groundhog Day.”

Fun film fact: Murray agreed to star in Ghostbusters if Columbia Pictures would make The Razor’s Edge. Ghostbusters was the biggest movie 1984, and The Razor’s Edge was a flop. Murray then took time off from acting, and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. Except for a supporting role in Little Shop of Horrors, he didn’t appear in another film until 1988’s Scrooged.

Murray was paid scale for Rushmore, but when the studio refused to pay for a helicopter shot Anderson wanted for the movie, Murray wrote a check for three times what he was being paid.

It’s fair to say that Murray’s shift from a character actor best known for his comedic roles to one of the great actors of his generation began with Rushmore. He received an Independent Spirit Award for the role and was named best supporting actor by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association, National Society of Film Critics, New York Film Critics Circle and others. Afterward, Murray went on to star in Hamlet, Lost in Translation, Broken Flowers, Get Low, Hyde Park on Hudson; he has appeared in every Wes Anderson film since.

Virtually every director and film fan loves Orson Welles, but he’s been a big influence on Anderson. The Magnificent Ambersons influenced The Royal Tenenbaums, but it goes deeper than that: “He’s not particularly subtle. He likes the big effect, the very dramatic camera move, the very theatrical device. I love that! And the also, he loves actors, and he is an actor himself, and he always created great characters that also tend to be larger than life.”

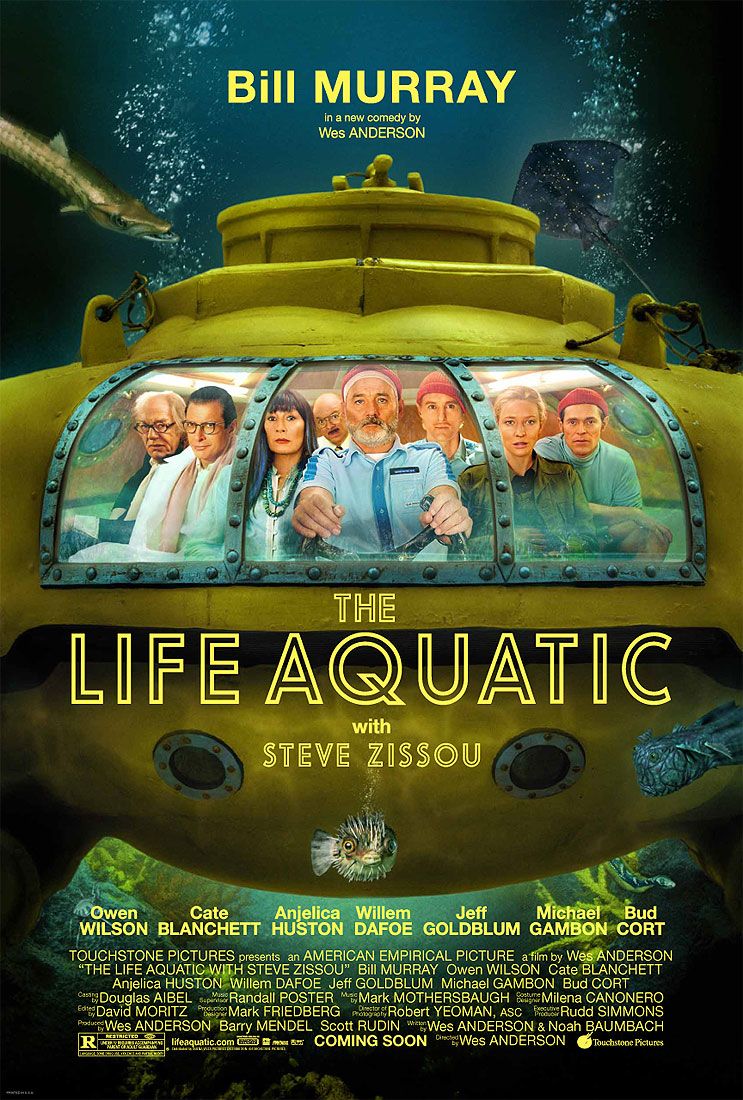

The book features a great description and analysis of 2004‘s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou: “a comic retelling of Moby-Dick with a key difference: In the end, the obsessed captain, who’s been chasing this beast that took away a part of him, stares the beast in the face and realizes it was nothing personal.”

This interpretation is epitomized by Zissou’s line when he sees the creature in the submarine near the end of the film: “I wonder if it remembers me?”

Anderson loves stop-motion animation, which is why he had the sea life in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou created by Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas, Coraline).

Anderson name-checks Rankin-Bass (Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer) and The Brothers Quay (Street of Crocodiles, The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes) when talking about stop-animation he’s enjoyed.

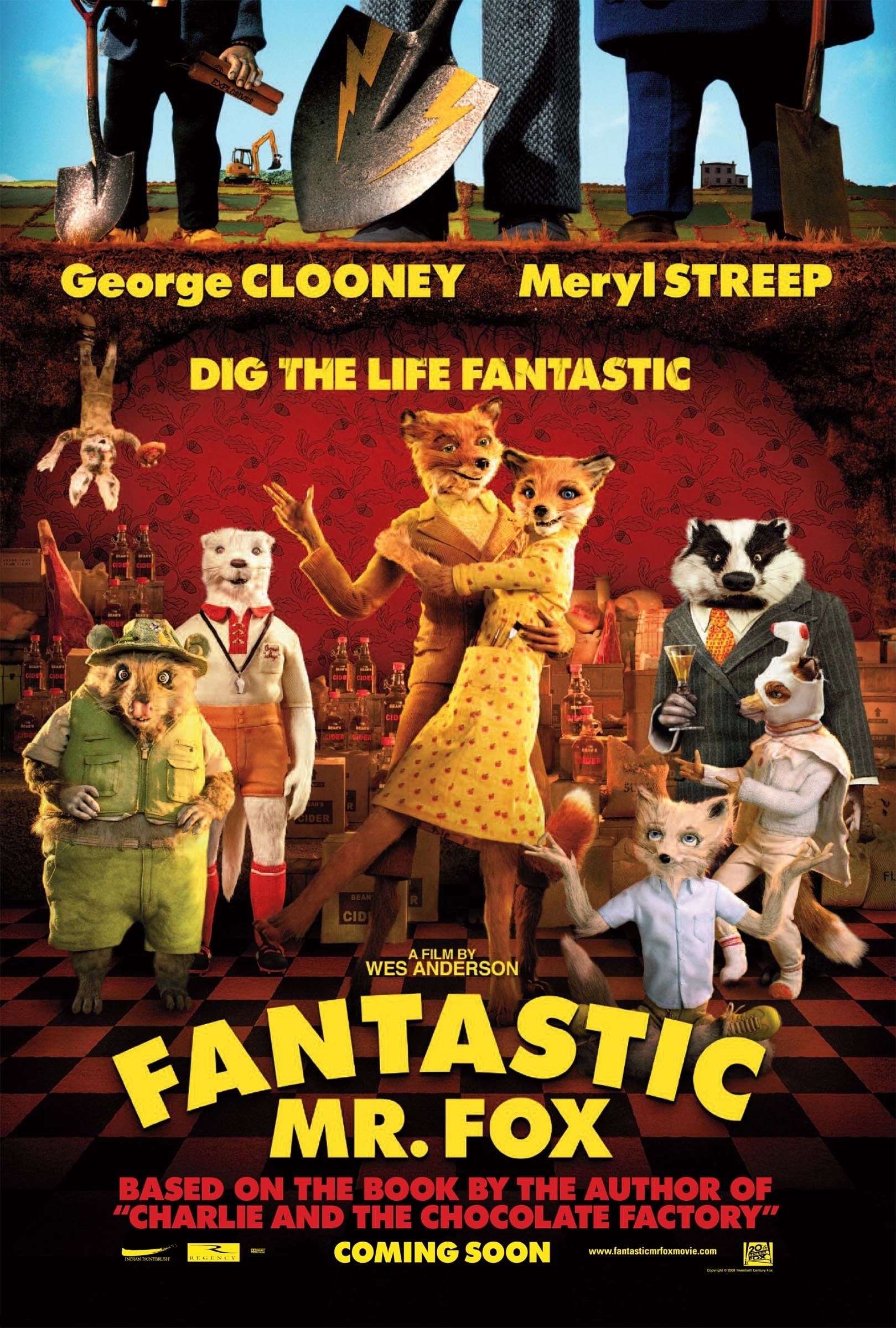

With his occasional collaborator Noah Baumbach, Anderson co-wrote and directed an adaptation of Fantastic Mr. Fox, the novel by Roald Dahl. Anderson, on remaining true to the novel even while changing and adding to it: “We decided Mr. Fox sort of is Dahl. Let’s say he’s kind of Roald Dahl, and let’s think of him that way. What would Dahl do if he were not writing this, but stealing these chickens?”

I never did get an answer as to why I think The Darjeeling Limited is such a deeply flawed film – and the least of all of Anderson’s work. Or a look at the many problems I had with Moonrise Kingdom, but I suppose that’s a topic for another book. Maybe one written by someone who’s less of a fanboy.

Unfortunately, Anderson’s films are not available for streaming on Netflix – or fortunately, as you would likely watch and re-watch the films intensely after reading the book. This isn’t a book to start on a Monday night and assume it won’t eat up a lot of your time. It will. Trust me.