A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

X-Factor #12-23 (Marvel) by Louise Simonson, Marc Silvestri (#12), Walter Simonson (#13-15, 17-19, 21, 23), David Mazzucchelli (#16), June Brigman (#20), Sal Buscema (#22), Bob Wiacek (#12, 14-15, 17-19, 21-23), Dan Green (#13), Joe Rubinstein (#16), Randy Emberlin (#20), Petra Scotese, Joe Rosen, Bob Harras

I tend to enjoy any comicbook that looks at the inescapable personal torments, damaged relationships, and psychological strains of the superhero lifestyle. Secret identities, an endless and self-feeding cycle of violence, taking on the impossible responsibility of keeping the rest of the world safe—it's bound to take its toll on anyone, and it's nice when a narrative acknowledges that. X-Factor #12-23 digs deep into these superhero problems and their consequences, then piles on several other whole sets of problems, too. There is, of course, the classic conundrum of humans fearing/hating mutants no matter what they do, which is amped up more than usual in this particular series because of its foundational concept of X-Factor pretending to be mutant hunters. Though less explicitly discussed, there's also an argument embedded in these issues that the whole idea of gathering mutants together and training them to use their powers and fight evil mutants might be flawed, that Xavier did both harm and good with the original X-Men and now, as X-Factor, those same characters are repeating his mistakes with a new generation. Then again, there's no better alternative offered here, because if not protected, nurtured, and taught control, the young mutants of the world could potentially do massive damage without even meaning to. So X-Factor presents a pretty dreary interpretation of the mutant-heavy reality of the 1980's Marvel Universe, one where there may not be any truly good choices for mutantkind to make, especially because, in that world, superpowers almost always lead to superheroics (or supervillainy), which in turn lead to their own significant stresses, injuries, etc.

To be fair to X-Factor, they don't actively encourage their young wards to participate in the superhero stuff, focusing more on the power control than the battling of baddies. Yet the kids get affected by it nonetheless, often the targets of the villains' schemes and always having to deal with the fallout from the heroes' adventures, even when not involved. The whole idea behind X-Factor as a team is that they pretend to be humans who professionally hunt and capture or kill mutants, when really they're mutants themselves who secretly rescue the children they're hired to go after, helping them learn how to better manage their abilities. Trouble is, the members of X-Factor have been active superheroes for so long, since they were still Xavier's students and the founding members of the X-Men, that they can't break away from that life completely to step into the role of teachers and guides. They find themselves fighting human and mutant enemies new and old all the time, never able to fully rest in between conflicts. This exposes the children, directly and indirectly, to all the violence and danger every superhero has to face, raising the question of whether or not they're truly any better off under X-Factor's care than they would be on their own.

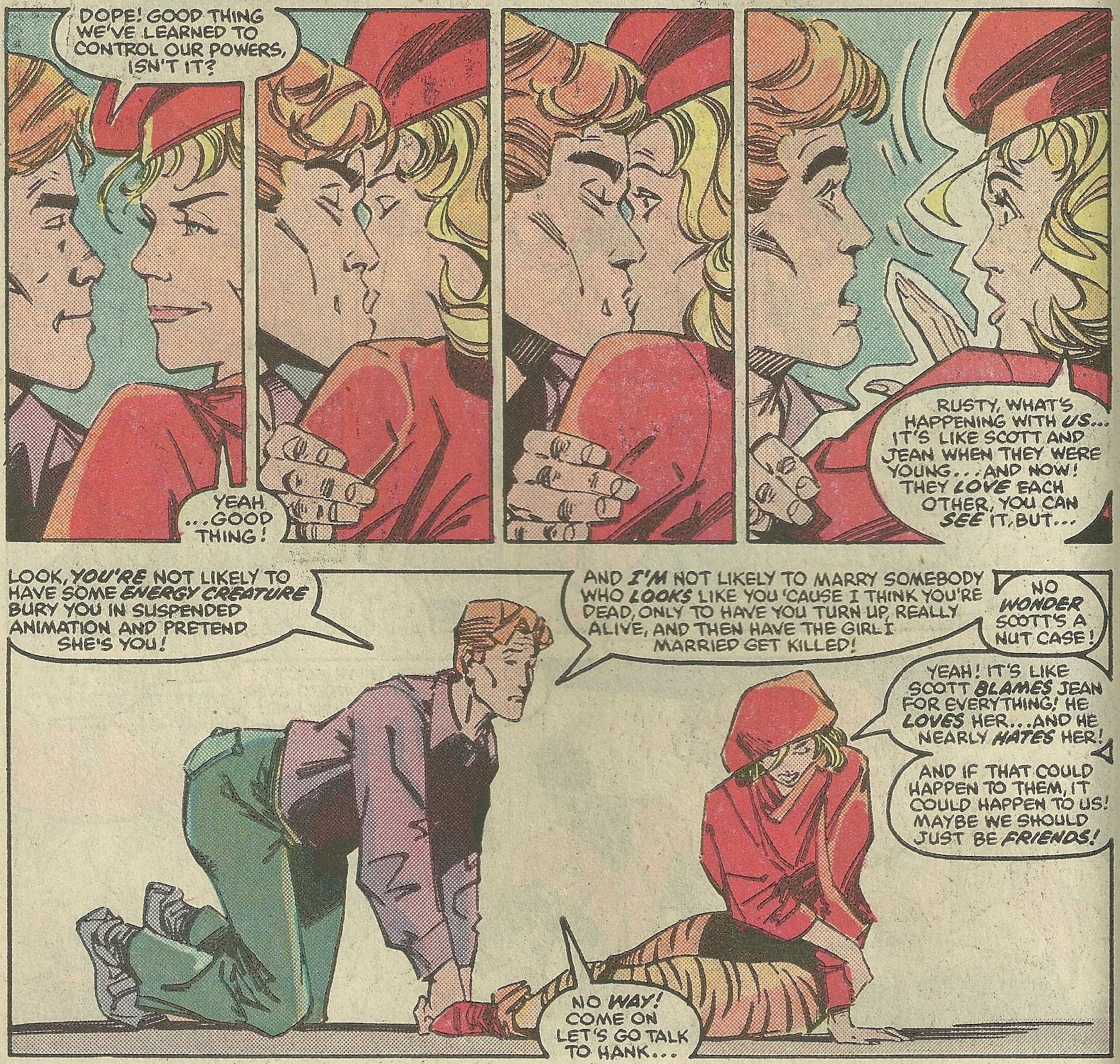

Some instances of the kids being in danger are glaringly obvious: they get kidnapped and tortured by anti-mutant group the Right, they fight for their lives against Masque in the Morlock tunnels, one or more of them loses control of their powers and puts the others at risk. Then there are the subtler things, like Rusty and Skids being afraid to explore their feelings for one another because they can see what has happened to Jean and Scott over time. They were into each other in their youth, but then Jean got possessed by the Phoenix, Scott got seduced by Jean as the Phoenix, and after the Phoenix made it look like Jean was dead, Scott married a Jean lookalike to try and fill the void. Finally, Jean returned, so Scott bailed on his wife and son, leaving both him and Jean with understandably confused and powerfully guilty feelings about the whole thing. That's hardly the kind of relationship history that someone should look at and think, "I hope that doesn't happen to me," yet that's exactly

Skids' concern when she and Rusty begin to fall for each other, because Jean and Scott are the only example she has of a mutant romance. Therein lies the true threat to the children in the long-term; it's not so much about putting them in the line of fire right now, it's more about the fact that, with X-Factor as their role models, guardians, and teachers, it seems unlikely that anything other than a life full of fighting and peril could possibly await these kids. They watch X-Factor do battle on TV or in person, then live through the aftermath of that whenever the team returns home, often having to help with healing or other post-combat duties. Costumes, codenames, and all the struggles that accompany them are normal for the kids, everyday and familiar, which doesn't bode well for their futures.

Because at the same time that we watch the young members of X-Factor's cast grow up in a superhero household, we also get five prime examples of just how messed up a person can be if that's the environment in which their raised. Scott, Jean, Bobby, Hank, and Warren were the first X-Men, spending their adolescence battling Magneto and using the Danger Room and all that jazz. Now, as adults, they all have deep-running and significant personal problems, making them unstable (at best) as individuals and as a group. At the beginning of this specific run of issues, Warren, a.k.a. Angel, has had his wings severely injured while saving the lives of several of the kids. He's in the hospital, and while his physical condition is bad enough, his mental state is far worse. He simply cannot cope with the idea of not being able to fly anymore, can't imagine life without the use of his mutation. The depression overwhelms him, and he lashes out at his teammates because of it, refusing to accept the idea that things might still turn out ok. Ultimately, his wings gangrene and the doctors remove them without his permission after the court declares him incompetent. This is more than he can bear, so Warren sneaks out of his hospital room and attempts to commit suicide. It doesn't work because Apocalypse intervenes, but everyone else believes Warren is dead and, either way, that's not the point. What matters is that he tries, that the thought of going on without his wings is so devastating to him, that it hurts and scares him so tremendously, he'd sincerely rather die. That's an unhealthy attachment to a single part of himself, his identity too wrapped up in his powers to survive without them, yet it makes a certain amount of sense considering his history. He's been Angel for so much of his life, and it's the role that has meant the most to him, that when he loses it he loses the rest of himself, too, and thus his will to live. Not exactly the best message to send to the kids he's supposed to be caring for, nor is it at all healthy or right for him to view himself as worthless if wingless. But it's understandable considering how integral to his whole existence those wings have been up to this point.

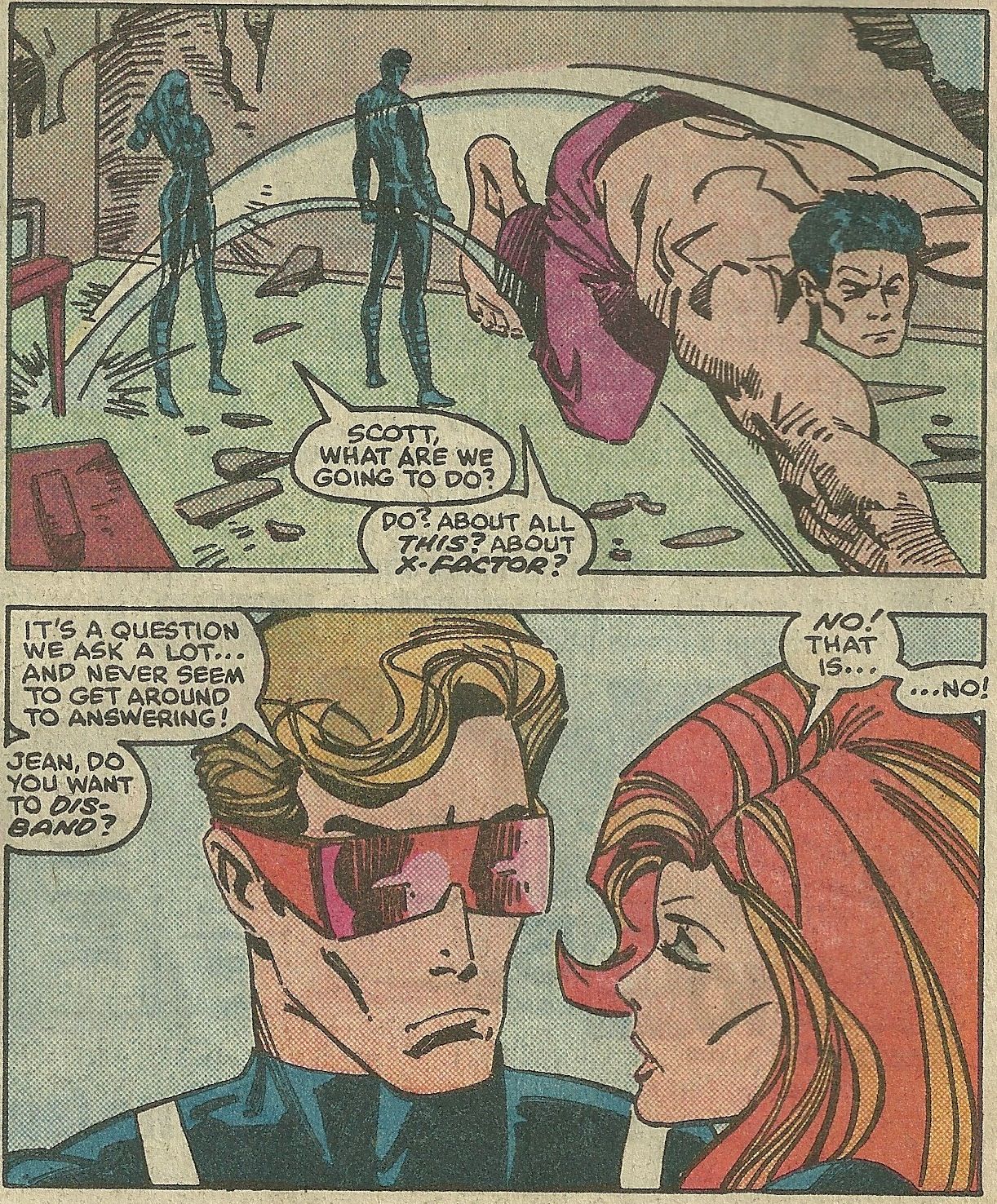

Cyclops/Scott's situation is even more complicated and painful than Warren's, probably the worst of the group. It has mostly to do with his tangled history with Jean, which is no surprise, and that history is very much informed by the fact that they are former teammates as well as lovers. Also, Scott leaving his wife Madelyne (or Maddie, as she's typically called in this book) when Jean came back from the dead was a decision motivated only partially by his leftover feelings for Jean, and just as much by the fact that he missed the life for which Xavier had trained him. He missed being a warrior, a leader, and a hero, admitting as much to himself when he goes back to his old home in Alaska to try and reconcile with Maddie. Being in the front lines of the mutant conflict is who he is by now, a part of his core, and he couldn't continue without it any more than Warren could live without wings. Except for Scott, returning to his old life meant abandoning a new one and hurting the people in it, and the shame he rightfully feels over that hangs over him always. It fuels him as he blames himself for everything else that goes wrong in his life, constantly why-me?-ing and I-should-have-been-there!-ing and all the usual martyr rhetoric. He's not entirely off-base. What he did to Maddie was despicable, and when he gets to Alaska he finds her gone and all traces of her somehow erased, and is subsequently shown a corpse by the police that looks very much like her. It's not her, because she's hanging out in hiding with the X-Men, but Scott believes his wife is dead and his child missing or worse, and the self-directed anger he feels over not being there to protect them is at least somewhat justified.

Where Warren tries to end it all for good, Scott keeps going, but in a perpetual state of despair and self-loathing. The levels of each rise and fall depending on what's going on, but he's never totally happy with himself or what's around him, and at times he starts to lose touch with reality. Some of that is due to antagonist Cameron Hodge's manipulation, but the reason it works so well is that Scott is already in such a vulnerable state after a lifetime of fighting the good mutant fight.

All of X-Factor are similarly fragile, though Warren and Scott are the most extreme cases to be sure. Bobby/Iceman's powers go out of whack because of something that happens to him in Thor, and his frustration over that also leads to him coming apart at the seams a little over the whole fake mutant hunter nonsense. The misguidedness of that plan is a major focus throughout these issues, actually, culminating with Hodge, who is X-Factor's head of P.R., being revealed as the leader of the Right, an organization of fanatics who want to use mutants as tools for humanity. Hodge's ad campaign for X-Factor as mutant hunters had been so inflammatory that the anti-mutant paranoia it caused had begun to outweigh whatever good X-Factor could do as a team, and everyone started slowly questioning if perhaps they had taken the wrong approach. Nobody questioned it more loudly or angrily than Bobby, which is a good instinct on his part, but his rage also highlights just how long X-Factor had let their failed experiment continue, how out of hand it got before any of them to realized it. This also underscores how ill-equipped they are to be helping the kids, too distracted by their own things and used to the chaos to see how poorly they're going after their goals.

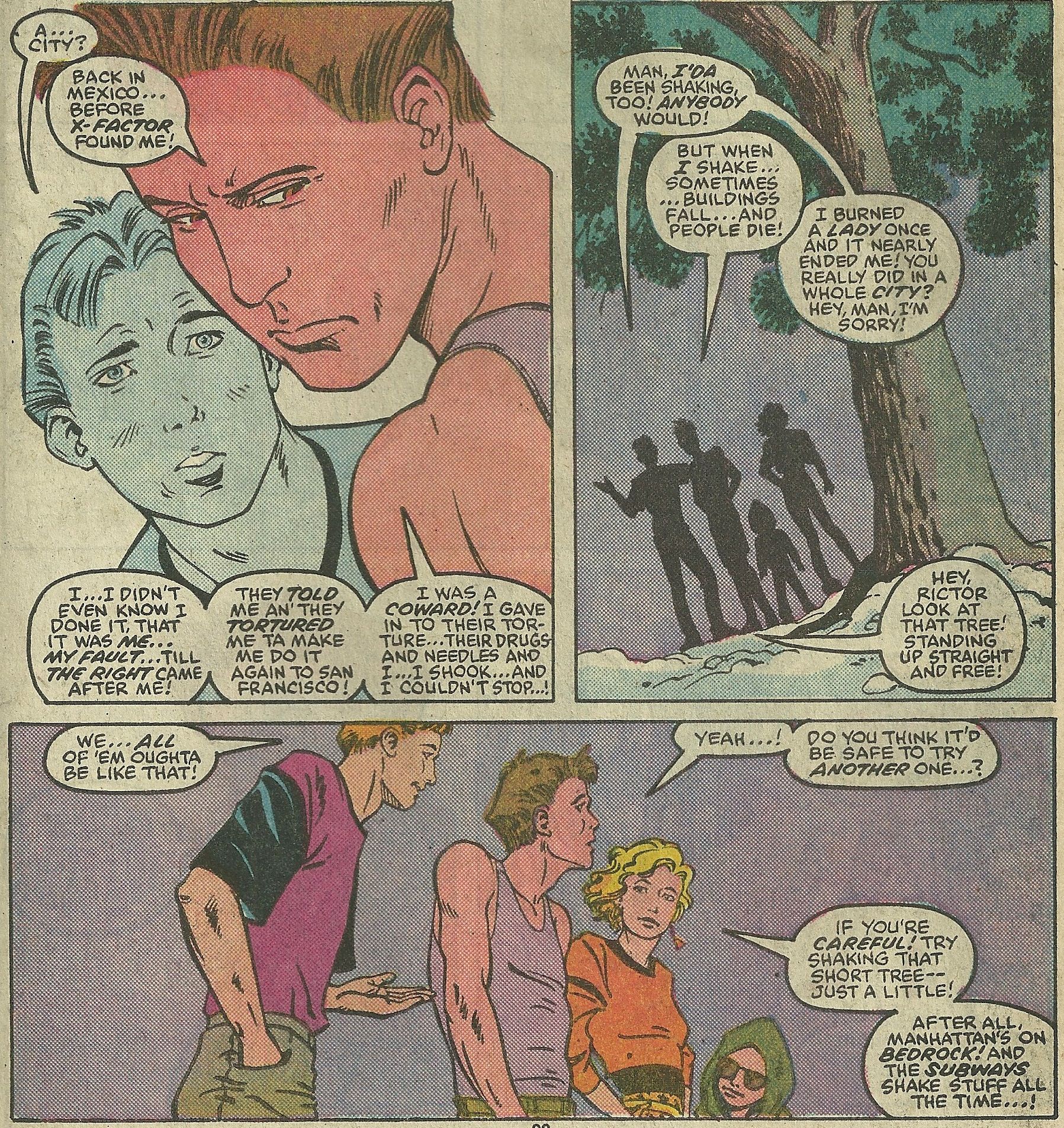

For all my criticism of X-Factor's behavior, and all the hypothetical harm they're doing to the children in their care, it still seems quite possible that this is the best any of these characters could have realistically hoped for. If X-Factor wasn't there to save them, most of the kids would be dead, except Rictor who would still be the Right's prisoner, forced against his will to destroy San Francisco and who knows how many other cities? The choice for these young mutants is to either be soldiers of good or victims of evil; in X-Factor, there is no space for neutrality. Maybe they're not doing great, but they're still alive, they have potential, they can rely on each other, and they do learn a few valuable lessons here and there, if only by chance.

When it comes to the grown-ups, perhaps the paths they walked made them crazy, maladjusted, and/or easily breakable, which means they don't always go about their good-doing in the smartest or safest way, but they live in a world that's often openly hostile toward them, and they keep striving to change that. Even if some of their attempts backfire, there's virtue in trying again, in the search for new strategies to improve the status quo.

As evidenced above, Louise Simonson unloads on her cast, a double-barrel blast of tragedy every month. Not only that, but she places them in a setting where that level of sadness and hardship is arguably a best-case scenario, the baggage ever good-hearted mutant must carry. She deliberately lays it on thick but avoids overdoing it, always providing a sliver of hope here and a half-victory there to make the reader and characters all believe that maybe, just maybe, things are going to turn around someday. That's never true, but Simonson can sell it over and over. There is definitely an over-abundance of characters reexplaining things to each other that everyone already knows, which was common for comics of the era, especially Marvel series, which wanted every issue to be new-reader-friendly. Other than that, Simonson writes an excellent mutant soap opera, following numerous threads and giving every character their own flaws and fears so everyone can have a turn in a custom-tailored hell.

Walter Simonson is the main penciler, usually inked by Bob Wiacek, and while they are a good fit, I actually preferred the work of some of the guest artists. Simonson and Wiacek's figures are sharp and angular, which brings out the seriousness and anger in the characters well, but those are only part of the whole picture. June Brigman and Randy Emberlin's work on issue #20

had more emotional range, and was therefore able to get more intimate with the cast. For example, though he's introduced three issues earlier, we don't really get to know Rictor until Brigman and Emberlin step in. Some of that is the story, more focused on the kids than adults all the way through that issue, but the expressive and close-up acting from Rictor under Brigman and Emberlin's hands is the key that unlocks him as a character.

All of the artists deliver reliably solid visuals, though, able to capture the heart of Louise Simonson's melodrama and the superhero action in equal turn. The scripts balance those elements nicely, too, not always within each issue but on the whole. And the Walter Simonson-Wiacek combination is extra strong when superpowers are going off, most notably Iceman's, so the primary art team brings a lot to the table, but they aren't quite at the top of my list for this title. And even at it's best, there's nothing mind-bending in this series. What's impressive about it is that it never slacks off or stumbles, which is a rarity that makes for a very rereadable comicbook.

It's also important to note that, other than Simonson, the only two creators to work on all twelve of these issues were colorist Petra Scotese and letterer Joe Rosen, both of whom bring a certain crispness to the book's final layers. Rosen's lettering is clear and well-placed, but most importantly, he's strict with the size of any given dialogue bubble, splitting longer lines into two or three connected bubbles rather than one large one. That keeps the pace up, and is rather useful during some of the characters' longer woe-is-me monologues. Scotese's coloring isn't flashy, but it's incredibly precise. She pays a lot of attention to lighting, and uses it to enhance the mood whenever she can, but doesn't stray into unrealistic or hyper-stylized territory. The down-to-earth colors add weight to the narrative, severity, as well as visually tying the book together through all the various artists.

X-Factor's not what you'd call cheery, nor is it even all that exciting, but it's a gripping, easy read that handles tragic content expertly. It manages to depict a destructive, dangerous, ill-conceived project like X-Factor as the best option, the least of all available evils. By the end of 1987, there was even some indication that it could be fixed, that a better version of X-Factor might be pulled from the wreckage of the awful first try. Then Apocalypse makes his move and the series kicks off 1988 with the "Fall of the Mutants" event, because anytime things look up for a second, they have to come crashing down harder than ever before. That's the rhythm of X-Factor, the most consistent rule under which it operates. Not designed to produce uplifting or inspiring stories, it instead gives the reader a look at people making the best of impossibly negative odds and circumstances, a bleak but fascinating study.