A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

Wild Dog #1-4 (DC) by Max Collins, Terry Beatty, Dick Giordano, Michele Wolfman, John Workman, Mike Gold

I have sort of a weird relationship with Wild Dog. Unlike most of the comics I review for this column, this is one I've read before. Multiple times, in fact. But I don't revisit this series because it's one of my favorites; on the contrary, I find it mostly disappointing, with too much wasted potential, mostly flimsy characters, and a glorification of violence that's extreme even for a superhero comicbook. Wild Dog is arguably not a superhero title since the main character has no powers, but if you put on a mask and have a fake name, you're a superhero in my mind. If Batman and Green Arrow count, Wild Dog certainly does. Anyway, my original point is that I'm not a very big fan of this comic, but even after all this time, I want to be a fan. I wish this book was better, meatier, more worthwhile. It seems like it wants to do a lot of things that I would really enjoy, but it never quite gets there, too trapped in its own weird structure and mixed-up priorities. There are ideas introduced here that I find interesting, but the story never goes deep or far enough with them. The biggest example of this is actually Wild Dog himself, a protagonist who we never really get to know, whose origin story is saved for the final issue, and who exists more as a narrative force than a full-fledged character. Without a hero to follow or care about, the series ends up being primarily about how the world reacts to someone who takes justice into their own hands, which is another concept that tickles my fancy, but that's also only superficially explored. Basically, all the stuff I want to see more of takes a backseat to long, unrealistic, visually strong but narratively non-compelling fight scenes, which is alright if that's what you're into, but only carries me so far. The violence becomes boring and repetitive before long, and is made all the more irritating because it keeps stepping on the toes of the development of better material.

Let's get this out of the way up top: Wild Dog is pretty clearly DC's answer to the Punisher. They are both war vets who lose loved ones to the mob and consequently become obsessed with killing criminals, so there's really no point in trying to deny that the one influenced the other. I'm not saying Max Collins and Terry Beatty explicitly set out to make another Punisher, though maybe they did, but whatever their original inspiration was, you just can't escape the similarities between the two characters. Even Wild Dog's hockey mask is reminiscent of Punisher's skull symbol. This isn't necessarily good or bad, but it's worth pointing out if only because it feels like the elephant in the room whenever I think/talk/write about Wild Dog. So now that I've acknowledged it, it'll be ok if I never mention it again in this post. Phew.

The first thing Wild Dog does that ultimately feels mishandled is its setting. The story takes place in the fictional Quad Cities, the importance of which is that it's middle America. So many U.S. heroes operate out of New York or a New York knock-off, and those that don't tend to simply be on the west coast instead, but Wild Dog is in his own little section of the country, a different kind of hero for a different kind of location. That's not a bad notion, and it frees the character from getting too wrapped up in the rest of the DC Universe's business, but overall the setting doesn't have much significance. In terms of the details of the story, it could pretty much take place anywhere, which is a shame. To pick a section of America that isn't given much attention in this particular genre and then do nothing with it is a missed opportunity. There's no sense of community, no real definition of what a typical Quad Cities citizen deals with every day. Gotham, Metropolis, New York 616---these places all have personalities of their own that influence and are influenced by their respective heroes. All Quad Cities gives Wild Dog is a blank slate, an unknown, inexact background in front of which he can be placed. Perhaps as a result, he's a pretty empty character, too.

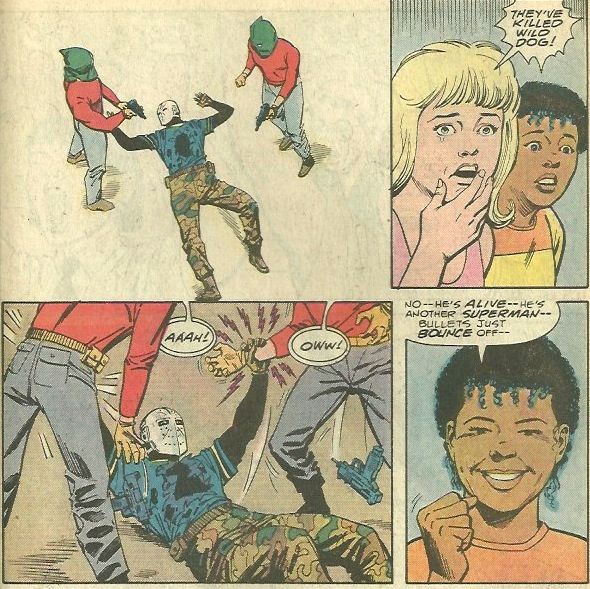

As I've touched on already, Wild Dog is the weakest single part of his own series. For the first 3 of the 4 total issues, we don't even know his secret identity, let alone why he does what he does. He is a faceless, near-wordless killing machine, a figure who comes out of nowhere and whose motives and goals are unclear beyond the fact that he wants every single bad guy to die as quickly as possible. This works in the debut because it allows Wild Dog to burst onto the scene in an exciting and mysterious fashion. And throughout the book, there's a throughline where several characters are trying to figure out Wild Dog's identity, so it remains hidden from the readers as well. The trouble with that, though, is it means all we know about Wild Dog for 75% or more of the story is that he chooses to mercilessly kill any and every villain he encounters, and that he will throw himself into battle at a moment's notice, taking zero precautions and risking tons of innocent lives in the process. We see a few more instances of Wild Dog wiping out groups of terrorists, but gain zero insight into what drives him to do so. His first appearance is enough to make me want to see more, but no more is offered for so long that, by the time the curtain is finally pulled back, I'm barely paying attention.

There are four characters presented as possible candidates for Wild Dog's secret identity, all of whom are friends from their college football glory days, and none of whom are very fleshed out. There's Lt. Andy Flint, a cop who we are told is a super hardass when it comes to cracking down on crime, even though we never see any evidence to back that up; Lou Godder, a newspaper reporter who we are told has a Pullitzer, but who we never see do any actual reporting; Graham Gault, maybe the most interesting of the group, an agent for the ISA, which is a liaison group between the FBI and CIA; and Jack Wheeler, local auto mechanic and the man who is actually Wild Dog. Somehow, local TV reporter Susan King manages to narrow down the suspect pool to these four men, although exactly how she does so is left largely up in the air. Gault, however, reaches the same conclusion, saying that all 3 of his old football chums have their own motives for being Wild Dog. Even this conversation doesn't take place until issue #3, and then issue #4 is primarily devoted to providing answers at last. Through flashbacks, we see that Wheeler was a marine whose whole unit was blown up by terrorists, and that he then came home and fell in love with a woman named Claire, only to see her gunned down in a drive-by shooting. Claire's death, it turns out, was a mob hit, as she was the only daughter of a deceased Chicago crime boss. Losing his fellow marines to terrorists and the love of his life to the mob is enough to break Wheeler, and he uses the money Claire leaves him to buy a bunch of gear and transform himself into Wild Dog.

It's not the best origin story, nor is it the most original or complex, but at least it adds up. I buy that the events of Wheeler's life might push someone to vigilantism, and that his athletic and military backgrounds would give him the skills to pull it off. The real problem is that this information arrives so late in the game, and once it's been revealed, literally as soon as we get official confirmation that Wheeler is Wild Dog, the series ends. So it's three issues of a hero we don't understand, then an issue to explain him, and then nothing. A small part of me appreciates that Collins tried something unusual, putting the origin story at the end instead of the beginning, but most of me just wishes it had come earlier so Wild Dog's actions would've had some context.

No innocents ever die or even get injured when Wild Dog is fighting the baddies, but he is definitely reckless with their lives, often going into hostage situations guns blazing without knowing the details of what's happening inside. He seems to trust himself to be so much better than all of his foes that he'll be able to take them down without any collateral damage, and he's always right. This hurts the arguments of the people who question the morality and/or righteousness of Wild Dog's behavior; in theory, they are right to be worried, but in practice Wild Dog always accomplishes exactly what he wants without any mistakes or serious fallout. Again, I think this is a misstep. He'd be a much more interesting character if there was a real conversation going on around him about whether or not it's right to do what he does. This discussion is paid some lip service in the comic, but it's always a surface-level debate at best, because as much as people might criticize him, he's getting precisely the results he's after. If anything ever went wrong for Wild Dog, even in a minor way, it would be easier for his detractors to make their point convincingly, and thus let Wild Dog as a series become a nuanced, multi-sided examination of the problems surrounding the use of violence as a solution to violence. Instead, the comic reads like pro-vigilante propaganda, because even with a few weak dissenting voices in the mix, the true message of this series is that if you're good enough with a gun, you can absolutely become a one-man judge, jury, and executioner, and you'll kill all the right people while keeping everybody else alive. That's a dangerous takeaway, and one I'd dislike from any book, but I'd be less bothered by it here if the counterpoint was given any support at all.

An inaccessible lead character, a smart setting that gets dramatically underused, and a lopsided central moral debate are Wild Dog's biggest flaws, or at least its most prevalent. And what bugs me about all three of those things is that it's easy to imagine them being handled better, thus making this a stronger book, because a lot of the fundamentals are solid. Terry Beatty's art, inked by Dick Giordano and colored by Michele Wolfman, is crisp and clean. It's not always the most fluid, meaning a few panels in any given fight scene might look a little stiff, but on the whole this is a good-looking comic. Each page reads smoothly, and there's a lot of great action stuff, classically badass without being too gory or ridiculous. And Collins' writing isn't terrible on a script level. Everything is easy to follow and understand, a simple tale told simply, and most of the dialogue sounds natural enough that it never takes me out of the story. So these creators have the smaller bit downs, and each individual issue reads like a serviceable if not groundbreaking bit of shoot-em-up comics fun. As a whole, though, this series flops, setting up too many things that pay off too late or not at all, ending in an intensely anticlimactic way, and generally dropping the ball on the execution of all its best ideas. I'd love to love it, but instead I'm left picturing a different version of it, the same basic narrative but delivered the way I wish it had been here, a dream of a comic that will never be.