A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

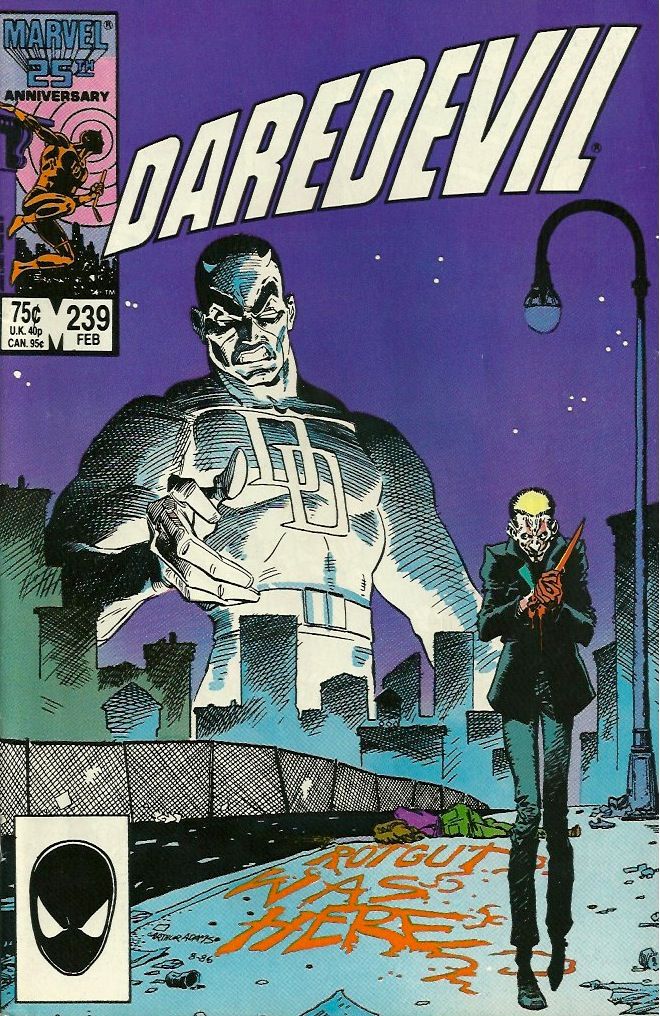

Daredevil #239-240 (Marvel) by Ann Nocenti, Louis Williams, Al Williamson, Geof Isherwood (#239), Max Scheele (#239), Bob Sharen (#240), Petra Scotese (#240), Joe Rosen, Ralph Macchio

Though not a great story by any stretch, there were two dominant themes in this pair of Daredevil issues that I always like to see explored, even if they're not handled especially well. The first is the notion of superheroes being as bad for the world (or worse) as the villains they fight. This was not a new idea in 1987, and it's been discussed many times since, but for any consistent fan of superhero stories (not just in comics but across all media) it's a point that bears repeated examination, because there is no wholly satisfying answer. Are the protagonists of these narratives really deserving of the title of "hero," or are they merely super-people fighting against other super-people in a self-fulfilling and never-ending cycle of violence begetting violence? The truth likely falls somewhere in between, and attempting to uncover it is a worthwhile activity.

The other of this story's themes that I so enjoyed ties pretty nicely into the first, and yet is still distinct and, in fact, a larger and more universal idea: everyone has their own perceptions of the world, and we are all both right and wrong. Some people see superheroes as the solution, others as the problem. Some think life is relentlessly miserable, some find it wonderful, and many can't make up their mind. The thing is, the way anyone interprets reality will also unavoidably affect the reality in which they live, meaning that their attitudes and opinions will help to justify themselves over time. This is not to say that every optimist has consistently great luck or every pessimist brings all of their misery on themselves; it's not nearly as simple as that. But to at least some small extent, we do all determine what world we live in based on what world we think we live in, our internal processes influencing our external circumstances all the time, and vice versa.

Daredevil #239-240 tells the tale of Rotgut, an odd and largely forgettable character, yet in some respects a perfect foe for Daredevil. Partially that's just because Daredevil is a street-level hero, and Rotgut is a street-level villain, a slasher with no superpowers. Beyond that, though, Rotgut works nicely opposite Daredevil because they're both hyper aware and analytical of the world around them. For Daredevil, this comes from his superior senses and radar ability, whereas for Rotgut it comes from his paranoid delusions, so it's not as if they notice the same things or form the same conclusions, but their shared attention to the details of their environments is something that bonds them and makes them interesting opponents.

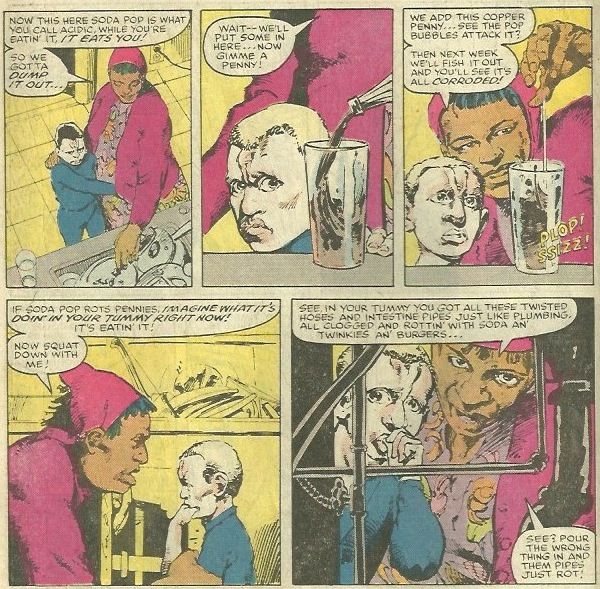

Rotgut was raised by an intensely germaphobic (and otherwise phobic) mother, who taught him that pretty much everything on the planet is dirty and dangerous. Being a child, he took her warnings to heart, but they also traumatized him. He internalized his mother's irrational fears and turned them into uncontrollable anger, a rage toward the filth of the world and all its people. We meet Rotgut when he's right on the brink, so fed up with the ugliness in everything he sees, and so revved up on

his own mania, he's close to hitting a breaking point. Inevitably, then, he does just that, trying to literally cut the bad parts out of people with a knife.

All throughout the story, the reader is tapped into Rotgut's thoughts, his incessant mental muttering, a running commentary on the horror he sees everywhere. A couple times it's even accompanied by a visual representation, the people he passes by resembling hideous monsters, the entire world distorted and threatening. We come to understand quite quickly the private hell he's in, and also why he's there, through a few key flashback scenes of him and his mother. I wouldn't call him sympathetic, necessarily, but he's certainly legally insane, legitimately believing he's helping to fight the good fight against the bad in all of us. When Rotgut and Daredevil eventually have their confrontation, the former compares himself to the latter, saying that they're both "heroes fighting disease." Daredevil the man disagrees, but Daredevil the comic lands more in the middle.

The first time Rotgut and Daredevil cross paths, it culminates in Rotgut's first attack, when he stabs and nearly kills a prostitute named Marsha. Daredevil tries to chase after him, but he's stopped by a group of men who either worked with or slept with or were maybe just friends with Marsha (it's not totally clear how they know her, but they know her). The group believes Daredevil to be Marsha's attacker, and even after he explains that it was Rotgut, they continue to fight him, saying that they don't need his help, that they don't want the destruction and danger that follow Daredevil and other superheroes wherever they go. It's a fair point, made fairer by Daredevil's response, which is to beat all of the men unconscious. Yes, it was self-defense, but if he could defeat them all in combat, he probably could've also just fled the scene. Maybe called the cops and reported Marsha's assault. Or an ambulance, for that matter. My point is, his attackers accuse him of making the streets more dangerous, and he proceeds to immediately prove them right by piling on more needless violence where his mere presence had already created it. Had he not been there to begin with, those same men could potentially have taken Rotgut down on their own, and maybe the deaths that came later would've been avoided. Daredevil even momentarily realizes his mistake after the fact, questioning how hurting people can be helping them. But he's fast to brush that aside as "dangerous thinking" and return to the task of chasing down his new bad guy, jumping right back into the superhero game rather than taking more than a minute to examine whether or not that's the right thing to do, big picture.

There's also the part where a young Daredevil fan knowingly allows a man to kill himself. In his first scene, Daredevil impresses and wins over a group of Hell's Kitchen youths called the Fatboys, which later leads to the kids following him to Rotgut's home, hoping they'll be able to help Daredevil with his heroing. And they actually do play an important role, warning all of the tenants of the apartment building where Rotgut lives that he's poisoned the water. All of the tenants except for one, a man who yells at and insults the Fatboy sent to his door before the child even has a chance to say his peace. The man happens to have a glass of the contaminated water in his hand, so the kid lets him drink it, and he subsequently dies. The closing panel of the whole arc is the kid, looking at the man's corpse under a sheet outside the building, and soaking up the reality and severity of being responsible, if only in part, for taking someone's life. Is Daredevil wholly to blame for this dark turn of events? Probably not, because he did tell the Fatboys they absolutely should not help him, but he isn't faultless, either. By choosing to interact with those children, he opened the window for them to be touched by his world, which is dangerous by definition, so it's a little irresponsible of him to do.

Daredevil, in his pursuit of doing good, does some bad as well. He definitely does more good and less bad than Rotgut on the whole, so they're not identical, but the gap between them isn't as wide as Daredevil wants to believe. Rotgut's comparison may be overly simplistic, but another way of saying that is it cuts to the heart of the matter, shining a light on the thing that bonds the two characters together. It's the reason they fight one another at all, really, each of them in the name of his respective cause. Daredevil tries to distinguish between them as fighting against something vs. fighting for something, but I'm not convinced. They're both fighting against something, it's just that the threat Daredevil's battling is completely real, while Rotgut's is largely imagined.

Not entirely imagined, though. Rotgut is way off about most of the specifics, but he's not wrong in saying that the world is dangerous, that there is filth, sickness, and death all around us. It's there if you want to look for it, easily found and abundant. At the same time, Daredevil is enchanted with the immense beauty of life, the music and motion of it. He experiences things on such a heightened level, he is more able to appreciate the tiny bits and pieces that make up existence, to enlarge them in his mind's eye and enjoy all the details individually. And he's not wrong, either. There is a great deal of wonder out there, in the extraordinary and the everyday, just as available as the dark stuff, and often found in the exact same places. Each character is wired to focus narrowly on certain aspects of reality, and in this case, it gives them contradictory viewpoints, but that doesn't mean one of them is totally right and the other wrong. They're just keyed into different truths.

As much as I like blurring the hero-villain line and celebrating opposing realities, there were some pretty big problems in how this narrative was delivered. Had their underlying concepts not been so right up my alley, I might well have hated these issues. Ann Nocenti doesn't bring a tremendous amount of subtlety to the writing, which is beneficial when it comes to Rotgut's semi-disjointed thought patterns, but more annoying whenever he and Daredevil interact and the lessons of the story are merely spoken aloud. Overly expository dialogue aside, the worst problem with the scripts is that a lot of scenes just don't go anywhere. The very first one, for example, is an effectively captivating and disturbing phone conversation between Rotgut and an unnamed woman. She's pregnant but still smoking cigarettes, which Rotgut somehow knows about her, and he lectures her about the dangers to her health and her baby's (among other things), in his own not-so-easy-to-follow way. That woman never appears again, nor are we offered any explanation as to how Rotgut knows the details of her life even though she doesn't know who he is at all. My best guess is that she lives in the same building he does...? That's just the first of several instances where something happens for no reason or is introduced without being resolved, and there really shouldn't be room for so much of that in a two-issue story.

My biggest complaint about these issues is also my biggest compliment: I wanted to see many, many more panels of Rotgut's perception of the world. Louis Willaims' art was pretty strong throughout the story, but the few times when we got to look through Rotgut's eyes and see his warped take on things were truly gorgeous in an unnerving way. Willaims can draw deformity and monstrosity so that it's attractive, even enticing. Still creepy and grotesque, but invitingly so. There wasn't nearly as much Rotgut-vision as there likely could and should have been, but the little there was went a long way in establishing him as a character and making him work.

It's no surprise that Rotgut didn't become a popular fixture in the Daredevil rogues gallery; as far as I can tell by looking online, Daredevil #239-240 were the only two comics in which he ever appeared. There's not a great deal of depth or mystery to him, because for the reader, all of his thoughts are right there on the page. His motives and goals are simple, and his methods as well, so I'm not sure how much more could even be done with him. Even this story might've fit into a single issue had it been more efficiently told. All the same, Rotgut worked for me, in his own right and in relation to Daredevil, and the story constructed around them was built on solid foundational ideas.