A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

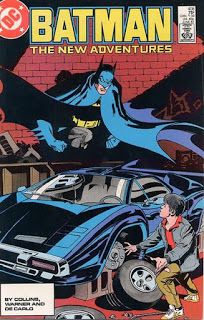

Batman #408-412 (DC) By Max Allan Collins, Chris Warner, Ross Andru, Dave Cockrum, Mike DeCarlo, Dick Giordano, Don Heck, Adrienne Roy, Todd Klein, John Costanza, Agustin Mas

I don’t know if Jason Todd ever stood a chance. At first, he was just a near-identical replacement for Dick Grayson when Grayson left the Robin game to become Nightwing. He was sort of a watered-down version of the young man for whom he was meant to stand in; the first Jason got the job done as Robin but offered nothing new, no reason for readers to warm to him or see him as anything other than a cut-rate attempt at recapturing the magic of the original Boy Wonder. So it makes total sense that in 1987 DC would take a stab at rewriting his background and personality in a post-Crisis world, providing an opportunity for Jason to carve out a more unique and possibly interesting space for himself in the Batman mythos. Sadly, though, I think they gave the task to the wrong guy, because Max Allan Collins wrote Batman as a lighthearted, almost goofy title, which did not really line up with the angry street youth persona of his revamped Jason Todd.

There’s too much silliness in the narratives that surround Jason’s introduction to take him entirely seriously. Yet he is so unstable and full of rage that he almost demands to be taken seriously anyway, to the point of sticking out as an abrasive and ill-fitting character in several places. Collins never marries the character’s attitude to the series’ tone, and that sets Jason up for failure from the get-go.

The basic concept for the character isn't terrible: a Robin with less self-control, but one more accustomed to hardship. Also more used to being self-reliant, which makes him less obedient but theoretically more capable in the long run. He's good enough to care for his dying mother for over a year, but brazen enough to steal the Batmobile’s tires, so it’s easy to see why Batman is so quick to take on this new ward. There is obvious potential for an exceptional Robin in a decent-hearted kid who also has familiarity with crime in Gotham and can hold his own in a fight. The problem is neither Batman nor Collins handle Jason the right way, so he has wild changes in mood and behavior that make him too unpredictable and grating to be a serviceable sidekick.

His meeting with Batman and ultimate recruitment as Robin connects to a forgettable plot about a nefarious elderly schoolteacher who uses her students to commit crimes. Ma Gunn is a laughable villain, puffing on a cigar and correcting her kids’ grammar in the midst of their criminal activities. Her evil side is revealed as the cliffhanger to Batman #408, where Jason is dropped off at her school and she sicks the other boys on him, saying, “Who wants to snuff the little stoolie for old Ma?” with a self-satisfied grin. It’s outrageous and overtly comedic, and continues through the next issue, culminating in her smacking Batman with her purse (even though she has a gun) when he interrupts a museum heist. It’s not at all a bad story, just a fluffy one, with relatively low stakes and a bad guy who never poses much of a threat.

And I think Collins was aiming for that with Ma Gunn. I think he was having a lot of fun getting to be the writer for Batman, so he cut loose and added a lot of humor to his short time on the title. In the next storyline, Two-Face commits a string of robberies, and the number-based puns saturate almost every page. From Two-Face working with the Dopple Gang to Robin saying, “He may be seeing double,” in the last panel of Batman #411, Collins lays it on thick, writing a comic book that has no desire to be grim or gritty in the least. Two-Face robs casinos and ballparks doing minimal damage, guns are drawn but rarely fired, and all of his henchmen are twins.

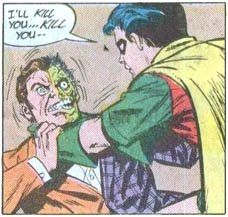

The problem with this approach, though, is that it leaves very little room to explore the deep and significant damage from which Jason Todd is trying to recover. You see this clash in the Ma Gunn story just a little, inasmuch as the severity of Jason’s life story—drug-addicted Mother and career criminal father both died, leaving him to fend for himself on Crime Alley— doesn't fully mesh with the levity of Ma’s whole shtick. But it really becomes a problem in the Two-Face story, which actually does attempt to further develop Jason’s history and identify some of his wounds, but can never fully pull it off because it still wants to be a comedy in the end. Jason, having recently discovered that Two-Face murdered his father, nearly strangles the villain to death, which is pretty much on par for an already short-tempered kid who was told he could be a superhero and then faced with his father’s killer. But there is no space in Collins’ script for Batman to address this incident appropriately, because by the end of the same issue Two-Face has to be defeated and Robin has to be an enthusiastic young hero again. Corny jokes about the number two don’t really fit next to in-depth conversations about loss and rage and revenge. So Batman just tells Jason that these are hard things to deal with for everyone, and then immediately says all is forgiven and takes the kid back into the field. It is rushed, irresponsible, forced, and unfortunate, and it completely explains to me why Jason never outgrew being a broken, unlikable rebel.

In his final issue on the book, Collins shifts his focus away from Jason almost entirely. Technically he’s present in Batman #412, but the story barely needs or uses him. Another none-too-impressive villain, The Mime, steals church bells, shoots a honking car, and disrupts a rock concert because she has an agenda against noise, and Batman effortlessly shuts her down. Robin assists, but his role is a minor one, and it adds nothing to his character. Not every story needed to center on Jason just because he was new, but it would have been nice if there were more than a single, two-issue arc with him as Robin before he became a supporting character.

This is all the work Collins would ever get to do with the boy hero he rebuilt, and it is sketchy and uneven at best. Though individually these issues make for humorous and fast-paced Batman tales, the overall portrait they paint of Jason Todd is too unclear and/or simplistic. Other than his short fuse and enormous baggage, we know very little about him, which is likely why those few elements became his defining characteristics. Collins did not give himself room to give Jason the space in which to grow, heal, or even learn, so he became trapped as an insolent punk. That’s not a guy people are eager to hang out with, and less than two years later, readers voted for his death.

It feels inevitable now that Jason would grow so unpopular so quickly, but I guess that’s only because I know that it happened. As shoddy as Collins’ establishment was, the character could have been salvaged in theory, made somehow redeemable by a clever transformative story. Instead, his wildness and fury were leaned into, a logical next step considering the direction in which Collins had been heading. It wasn't just that Jason was angry, but that even under the tutelage of Batman he had no fitting outlet for that anger, no means of facing his true problems and moving past them. You can’t just keep throwing a berserker into fight after fight with the hopes that eventually he’ll run out of rage. That’s not how violence or anger operate, and it certainly isn't the kind of training or therapy Jason needed. But Collins’ style on this book had no place for truly deep, painful, emotional storytelling, so even in his short time at the helm he managed to make Jason quite the stunted, damaged young man.

But at least Collins had a good time doing it, which is evident throughout. It’s important to see the lighter side of Batman once in a while, and remember that good and interesting stories can be told through him without all the brooding doom and gloom. If only these issues did not try to simultaneously introduce a kid bursting at the seams with doom and gloom, I think they’d be far more successful as a run. Perhaps Jason would have been more successful as a character, too, if his retooling had been handled with a little more depth and care. We’ll never know, and now the poor guy is the poster boy for DC’s teenage angst. His first misguided steps down that road began here, back in 1987.

NOTE: An earlier version of this review appeared on The Chemical Box